What Congress Can Learn from Social Workers About Workplace Safety

As Congressional offices prepare to open to the public for the first time since the pandemic and with the January 6th attack still very much top of mind for many staffers, we turned to the National Association of Social Workers to learn from the experience of social workers.

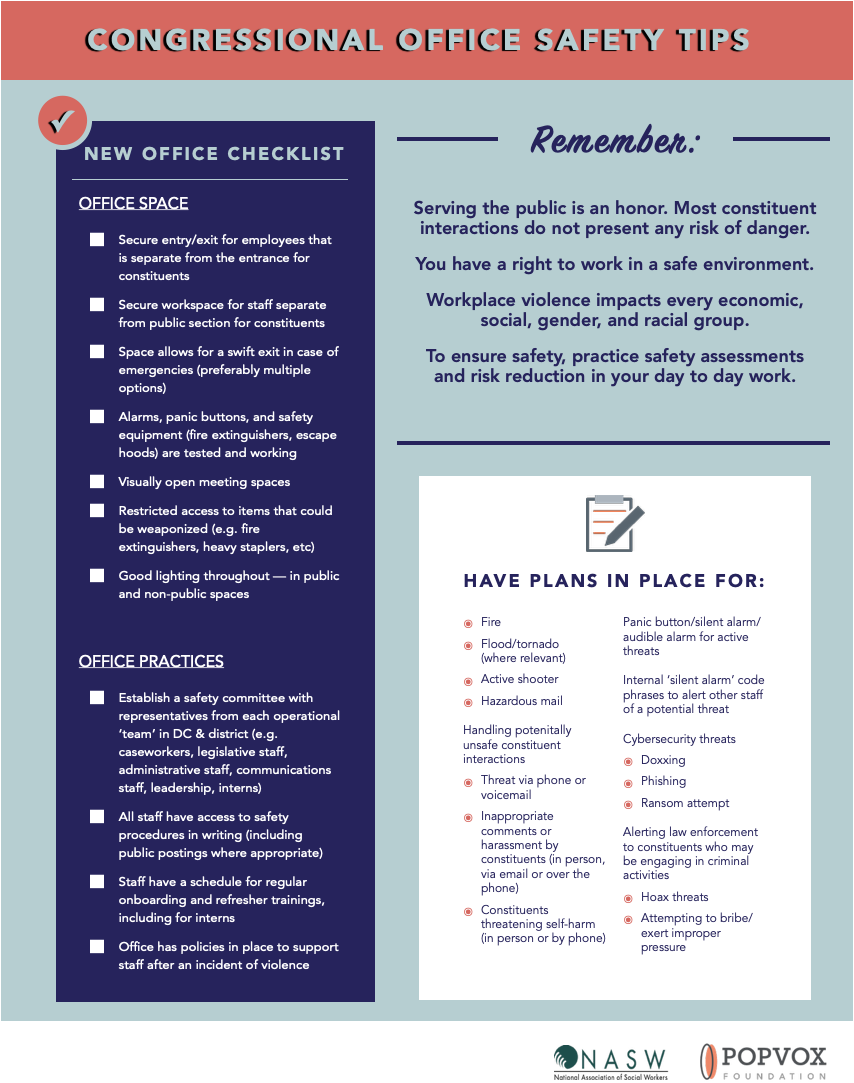

Click here for a printable checklist for Congressional offices from NASW’s safety guidance.

Reassessing Congressional safety after Jan 6th

With all of its glorious unpredictability, assisting the public is the cornerstone of what Congress is and does. Witnessing the grace and wisdom that constituents bring through some of their most challenging moments is one of the privileges of the job; working on their behalf is an honor. That said, as we’ve seen throughout the last year and in particular on January 6th, the job is sometimes dangerous.

Lack of standard protocols

As the often-mentioned “500 small businesses,” individual congressional offices are all finding their own ways to handle day to day operations and logistics. Important protocols, including policies and practices that ensure staff and constituent safety, are insufficient in many offices.

Psychological and Physical Safety on the Job

A major part of the job of a congressional staffer — especially junior staffers and interns — is to process constituent mail, answer calls and take constituent meetings. While most interactions are professional or even warm, it is not uncommon for callers or letter-writers to be frustrated or calling to “vent” about issues on which they disagree. Those interactions often turn personal or confrontational, and many offices fail to support staffers on the receiving end of the criticism or abuse. These interactions have long been treated as “rites of passage” for junior staffers, who are often treated as expendable or easily replaced if they are not comfortable putting up with verbal abuse or harassment.

While a lack of standard protocols and a high tolerance for unpleasant interactions have been more the rule than the exception for Capitol Hill over the decades, the events of January 6 showed that more effort and resources must be dedicated to staff safety.

Learning from experts: the National Association of Social Workers

For advice on steps congressional offices can take as they open their doors to the public post-pandemic, we reached out to the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) to learn from the experience of social workers. There are many parallels between social work practice and some types of Congressional work, especially casework. Social workers provide services in the community, across many settings. Social workers work in nonprofits, clinics, schools, hospitals, child welfare agencies, courts and many other settings, where they assist clients with a range of problems, often linking them to resources and services.

Beyond task similarities, there are structural ones as well: the NASW supports a distributed body of trained professionals with a vast array of specializations, and roles, much like Congress.

“The primary mission of the social work profession is to enhance human well-being and help meet the basic human needs of all people, with particular attention to the needs and empowerment of people who are vulnerable, oppressed, and living in poverty. A historic and defining feature of social work is the profession's focus on individual well-being in a social context and the well-being of society. Fundamental to social work is attention to the environmental forces that create, contribute to, and address problems in living.” — Preamble of the NASW Code of Ethics

NASW’s Guidelines for Safety are based on three principles that provide a helpful framework for staffers interacting with the public:

1) Acknowledgement of the Context of Work:

“These guidelines address safety and risk factors associated with social work practice, but they should not be interpreted to infer that social work is an inherently or unusually dangerous profession. Social workers acknowledge and understand that interaction with clients is a cornerstone of many practice settings. Most clients and families that social workers serve do not present threats or pose danger.”

2) Right to Report Safety Concerns:

“Social workers have the right to work in safe environments and to advocate for safe working conditions. Social workers who report concerns regarding their personal safety, or who request assistance in assuring their safety, should not fear retaliation, blame, or questioning of their competency from their supervisors or colleagues.”

3) Application of Universal Safety Precautions:

“Violence can and does occur in every economic, social, gender, and racial group. To avoid stereotyping particular groups of people and to promote safety, social workers should practice safety assessment and risk reduction with all clients and in all settings.”

These principles are not only applicable to a Congressional context, but vital for developing a set of sustainable safety policies that respect the dignity of the constituents, interns, and staff who come into contact with the office.

Planning Ahead for Congressional Office Safety

The “Congressional Office Safety Tips” document below draws from the NASW’s Guidelines for Social Work Safety in the Workplace to offer practical steps that offices can take to ensure that physical spaces are safe, staff is well-trained, and that they are learning from each incident to strengthen safety policies. For additional information, consult the NASW manual and NASW Code of Ethics.

***

Anne Meeker is a former District staffer, and Director of Strategic Initiatives at the POPVOX Foundation. Thanks to Sarah Butts, MSW, Director of Public Policy for the National Association of Social Workers, and Anna Magnum, MSW, MPH, Deputy Director of Programs for the National Association of Social Workers, for their insight and contributions.