WHITE PAPER

Institutionalizing Deeper

Public Engagement in

U.S. Policymaking

This is the first paper in the POPVOX Foundation’s “21st Century Engagement” practice area.

Chandra Middleton,

Ph.D., J.D.

Marci Harris,

J.D., LL.M.

The United States has a rich history of embracing public participation and input in the policymaking process. From the “Right to Petition,” enshrined in the First Amendment and the notice and comment requirement for federal agency rulemaking under the Administrative Procedure Act, to the constituent-focused operations of most Congressional offices and the public comment procedures in state and local legislative bodies, Americans do not lack for opportunities to make their voices heard. It is becoming increasingly clear, however, that existing systems are insufficient to the expectations of a 21st century public and the needs of a 21st century democracy.

In a 2020 report, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) described a growing “deliberative wave,” whereby countries around the world are adopting “innovative ways of involving citizens in the policy-making cycle.” The report suggests that institutionalization of these practices “can potentially increase trust in government, strengthen democracy, and enrich society’s democratic fitness by creating more opportunities for more people to significantly shape public decisions.”

The American Academy of Arts & Sciences empaneled a bipartisan commission in 2018 to provide recommendations for “reinventing American democracy for the 21st century.” The group’s final report, “Our Common Purpose,” included six pillars, among them “ensuring the responsiveness of government institutions” — with suggestions that referenced “deliberative wave” models, such as making public meetings more accessible, creating citizens assemblies, and increasing participatory governance.

Increasingly, the public expects greater opportunities to participate. This is partially due to commercial and social use of technology that makes it possible for us to weigh in on everything from our experience at the restaurant down the street to commenting on absolutely everything via social media; the use of social media is now “central to many people’s social lives” (Marwick at 2). Political scientist Francis Fukuyama recently noted — in the context of two infrastructure projects (Stuttgart’s high-speed rail terminal and Toronto’s “smart city” initiative) that met with massive public pushback due to mistrust and ineffective consultation processes — that:

[c]itizens demand a much higher level of active participation in governance, not just through voting but by helping to shape detailed proposals, setting budgets, contributing ideas, and, if necessary, publicly protesting against outcomes they don’t like... They also care intensely about the form that participation takes. (emphasis added)

Rising expectations for deeper, more productive engagement come at the same time questions are being raised about how justice and fairness are prioritized in our social, economic, and civic lives, with an emphasis on ensuring that traditionally underserved populations are included. And governments are responding.

On Inauguration Day, President Biden signed an executive order “advancing racial equity and supporting underserved communities,” that included a specific direction for agencies to “consult with members of communities that have been historically underrepresented in the Federal Government and underserved by, or subject to discrimination in, Federal policies and programs.” The resulting request for Information and subsequent report from the Office of Management and Budget states that, “the Federal Government needs to expand opportunities for meaningful stakeholder engagement and adopt more accessible mechanisms for co-designing programs and services with underserved communities and customers.”

On Inauguration Day, President Biden signed an executive order “advancing racial equity and supporting underserved communities,”

As the “deliberative wave” reaches our shores and the current administration encourages agencies to incorporate participatory processes into their work, it is increasingly important to examine the goals of these practices and how they can be employed across the policymaking continuum.

“Rising expectations for deeper, more productive engagement come at the same time questions are being raised about how justice and fairness are prioritized in our social, economic, and civic lives.”

Public Participation and the “Policy Continuum”

Abstract discussions about public engagement often conflate or ignore where the proposed engagement falls in the “policy continuum,” which spans from issue identification and policy formation through implementation, enforcement, and oversight. Each stage has its own procedures that inform how the policymakers and civil servants conduct their work. For example, Congressional offices and committees are constrained by the rules of each chamber. Regulatory agencies must follow administrative guidance. The Judiciary has rules of evidence and procedure that guide how court cases are undertaken. Public engagement happens in different ways, with different levers and potential for impact, at each of the different stages.

Robust engagement works best when the reasons for it align with the stage and function of policymaking to which it is attached. What kind of input, data, or knowledge is being sought (and why) must also be determined, in conjunction with the stage and function.

Participation at Each Stage of the Policy Continuum

Can policy outcomes be improved by talking with and listening to people who have previously been excluded? Can new processes help government address historical inequities and better anticipate future needs? Will more engagement lead to improved democracy? How can we contextualize 21st century expectations of justice, fairness, and improved policy outcomes when the government is working with 20th century technology and laws, both of which encode outdated understandings of justice?

According to the Centre For Public Impact, many characterize interactions with government as lacking humanity, empathy and authenticity. “‘Humanizing’ these interactions — even by demonstrating that ‘real people’ are behind government processes — can strengthen social cohesion and improve the perceived legitimacy of governing institutions.” “When conducted effectively, deliberative processes can lead to better policy outcomes, enable policy makers to make hard choices and enhance trust between citizens and government.” More robust engagement opportunities offer the potential to grow trust in governing institutions at a time when trust in government is at historic lows.

“‘Humanizing’ interactions with government — even by demonstrating that ‘real people’ are behind government processes — can strengthen social cohesion and improve the perceived legitimacy of governing institutions.”

While there may be emerging agreement on benefits of engagement in the abstract, those within government aspiring to make their own processes more participatory must be clear about the goals of engagement and how the goals relate to the particular process in question. For example, is the process a legal requirement, such as during notice and comment rulemaking? Is the engagement intended to identify problems that need legislative solutions? Does the engagement aspire to build relationships with communities to better understand their needs and ideas? Is it to offer an opportunity for Americans to fulfill civic responsibilities beyond voting at the polls? To provide a layer of oversight of government processes?

Public engagement may be undertaken for any or none of the reasons listed above, but it is essential that the initiating agency, office or policymaker understand the “why” in order to select the most effective process and evaluate its success. And the answer to the “why” question will be heavily influenced by where in the process the engagement occurs.

The Legislative Stage

Engagement that occurs in the legislative stage — this is primarily issue-identification and crafting legislation — often responds to lawmakers’ desire to be seen as responsive to their constituents. Some of the most familiar examples of civic engagement involve people writing to their lawmaker on an issue they care about, attending a town hall meeting, taking part in a “fly-in” day coordinated by advocacy groups on a particular topic. This constituent-to-lawmaker interaction is the bedrock of representative government and much of the operations within Congressional offices revolve around receiving and responding to constituent input.

Increasingly, however, individuals are becoming disillusioned with the lack of efficacy they feel when their participation is limited to a simple “call your lawmaker” action. Intractable partisanship and the rise of nationalized campaigns and powerful interest groups mean that individual lawmakers are less swayed by constituent input than they were in the past. And even if constituents manage to change the mind of one lawmaker, they still exist within a gridlocked system in which fewer bills are drafted by rank and file members and increasingly legislation occurs through massive must-pass packages that are negotiated by leadership.

“Robust engagement works best when the reasons for it align with the stage and function of policymaking to which it is attached.”

This top-down legislative process can alienate allies and fuel mistrust and apathy in the public if there is no way for their views to legitimately be considered. While input from the general public may be less relevant for some issues than others, there are some policy areas that cannot be sufficiently addressed without a process that includes input from those whom the policy affects. Rep. Raúl Grijalva, [D, AZ], chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, encountered this problem when he began to craft a bill to address environmental justice (EJ) issues. He describes how he “thought he had introduced the perfect bill” (in 2014) but “it languished because people didn’t feel invested in it… I learned a lesson there — that the process, and particularly on a piece of legislation as delicate and sensitive as environmental justice issues are, that we had to, we had to get the buy-in, we have to be inclusive [from] the beginning.”

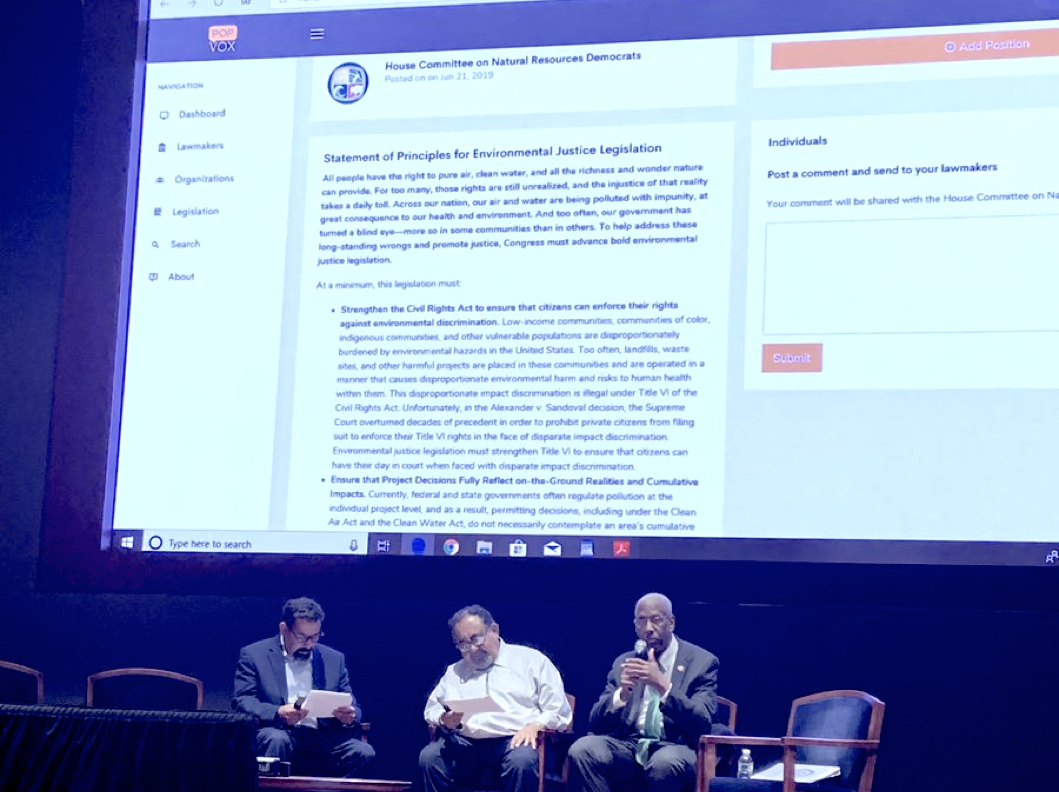

Grijalva and colleague Rep. Don McEachin [D, VA] took a different approach when they began drafting a new environmental justice bill in 2019, determined to “[have] the input of the communities most affected by the legislation” “at every step of the process.” The lawmakers began by convening a “working group” of environmental justice organizations who were invited to join an in-person and online “EJ Convening” with presentations and discussions about EJ issues. At the event, the committee launched a “Request for Input” process — open for several months — inviting individuals and organizations to weigh in on guiding principles for the bill before any legislative text was drafted. The committee took the input they received and incorporated it into a first draft of legislative text that they made available for inline comments on particular words or sections, and received over 360 substantive comments. The committee then incorporated the input they received into legislative text that was introduced as H.R. 2021, and they continue to solicit input on the bill through virtual town hall meetings and digital commenting opportunities.

The Regulatory Stage

Once a statute is enacted, executive branch agencies implement the relatively-broad policy. Public engagement becomes governed by agency political leadership and the legal requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). Created in 1946 to standardize how agencies went about their work at the time when each agency had its own way of doing things, the APA requires federal agencies to undertake “notice and comment rulemaking” when drafting most regulations, or “rules.” Generally: If an agency wants to create a regulation, it must share a draft of the proposed regulation with the public, offering the public time to submit written comments on that draft. The agency must then take those comments into consideration as it considers the final policy and drafts the final rule.

Different kinds of comments work within the government in different ways, so comments can be categorized by their effects on and beyond policymaking. Comments that influence the specific policy in the final rule tend to be of a technical nature and are often, though certainly not always, written by people who can speak to the legal, economic, scientific, or public policy dimensions of the proposed rule. Such comments might identify case law that suggests the proposed policy is an overreach, offer scientific research the agency might be unaware of, or offer insight into how a small business might be affected by compliance with the new rule.

Mass comments also receive a lot of attention in conversations about notice and comment rulemaking. Mass comments can be in the form of a petition: One message with hundreds or thousands of names attached. Or, some advocacy campaigns encourage their members to submit comments individually. Mass comments rarely affect the specific policy proposed in the rule, in part because they are not specific enough. They can, however, operate beyond rulemaking by creating buzz around a particular issue, bringing political attention to it that might subsequently affect how that issue is handled by Congress and regulatory agencies.

In the early 2000s, the notice and comment process shifted from a predominantly paper-based endeavor to an online portal, ostensibly allowing for more and easier participation. Simultaneously, the rise of the Internet allowed an ecosystem of advocacy groups to initiate online campaigns, rather than letter-writing campaigns, that delivered comments with the click of a button.

While such campaigns make it easier for some to opine about agency action, technological, social, and economic barriers persist for people who have traditionally been excluded: 1) most people do not know what notice and comment rulemaking is, much less that it is something they can participate in; 2) Internet access--all but required to learn of a proposed rulemaking and to use online portals to submit comments--is not equitably distributed across the country; and 3) nor is leisure time to research and write a comment equitably distributed.

The opportunity to comment online raises obstacles for agencies, as well. Beth Simone Noveck notes that, today, “the process of public commenting provides a vital opportunity for agencies and Congress to obtain important and relevant information from diverse audiences that will help them to understand whether and how a regulation fulfills its legislative purpose.” This data-gathering is intended to make sure the agency has the best and right kind of information it needs to decide on the best approach to reach statutory policy goals. Yet, agencies are being stretched thin by comments that do not fit with the data-gathering function the government assigns to notice and comment rulemaking.

“A more deliberate inclusion of public input ... could open doors for early identification of what is or is not working, demonstrate to the public that their experience and input matters, and allow for collaborative refinement of policy for greater effectiveness.”

An oft-cited example comes from 2017, when satirical television host John Oliver urged viewers of Last Week Tonight to submit comments to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in support of net neutrality protections. The public response of approximately 22 million comments overwhelmed comment portals and internal systems by which comments are processed. While most rules do not receive so many comments, the increase in number and types of comments received since going digital has been substantial. Agencies are already burdened with trim finances and resources. How will they receive, process, and make sense of even more data and more diverse types of data? Financial considerations are a critical component of increasing engagement.

Agencies are now also addressing problems unique to the online space. The opportunity to submit comments anonymously leaves open the potential for mass fraud, as was seen in the FCC net neutrality rulemaking. Further, while the potential policy effects are likely to be limited for the foreseeable future, civil servants are now forced to deal with the possibility of non-human voices in the form of artificially-intelligent bots that are programmed to submit comments. Agencies are grappling with how to address these concerns, while not freezing participation in online notice and comment rulemaking.

While the government understands notice and comment rulemaking as a data-gathering process, the public increasingly understands it as a way to voice their opinion about the general policy direction motivating the rulemaking. The process seems to be broken. Indeed, there are ongoing conversations about how to fix the notice and comment rulemaking process. But, once understood as only one part of the policymaking continuum, it becomes possible to imagine fixing notice and comment rulemaking by offering the public opportunities to voice their opinions elsewhere on the policymaking continuum. Importantly, those other avenues for expressing opinion can be much more worth the effort if they are well matched with the development of policy.

Engagement Outside of the Traditional Policy Continuum

At which points in the policy continuum should engagement be sought? Traditionally, advocacy has occurred once the “cake was baked,” with the public weighing in on whether their lawmakers should support or oppose a particular bill that has already been introduced. Similarly, in the regulatory notice and comment stage, the policy has already become law and the agency has a rough idea of the rule they want to enact, so public engagement has a relatively narrow opportunity to actually affect the policy. Would public engagement be more productive— and satisfying for participants — if it came earlier in the policy continuum, perhaps on emerging issues that fall into what Anne-Marie Slaughter of the New America Foundation has described as “pre-partisan” issue?

One example of how this might work is the consultation process of “public technology assessment (“pTA”) employed by the Expert and Citizen Assessment of Science and Technology (E-CAST) network at Arizona State University. To date, the E-CAST network has hosted peer-to-peer deliberations on issues such as planetary defense with NASA and climate resilience with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). These deliberations pair experts and citizens in a multi-stage, iterative process that informs citizens while soliciting their input, often before policymakers take up the issue.

As previously mentioned, the innovation of the participatory process for drafting the Environmental Justice for All Act began with bringing affected communities in early, before bill language was drafted. The EJ Working Group included organizations that have not traditionally been part of the legislative process in such a direct manner. Initial feedback suggests that the process improved participants’ understanding of how bills are crafted, facilitated meaningful interaction among groups with diverse ideological perspectives, and improved staffers’ understandings of how proposed language would work in the real world.

Federal agencies also gather information before policies are drafted. For example, in some cases, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is required to consult with Tribal authorities and, stemming from Executive Order 12898, environmental justice communities before policies are drafted.

If there is value in public engagement in the early stages of policy development, what about the post-implementation stage? Government agencies are notorious for their relatively minimal “lookback” processes to determine whether policies are implemented as intended or if actual impact aligns with congressional intent. Often the only tool for evaluating program success is a report by oversight agencies such as the Government Accountability Office or inspectors general. In most cases, these oversight processes do not include engagement with affected communities to include how policy implementation affects real people. The still-nascent implementation of the Foundations in Evidence-Based Policy Act may open doors for academic studies — which might include interviews or other qualitative research — to be considered as agencies evaluate policy effectiveness. A more deliberate inclusion of public input, however, could open doors for early identification of what is or is not working, demonstrate to the public that their experience and input matters, and allow for collaborative refinement of policy for greater effectiveness. Whether this kind of engagement is initiated or hosted in the agency or by Congressional committees as part of their oversight duties is an open question and ideally, it could be useful to experiment with pilot processes in both areas.

Of course, there is one well-developed area of post-implementation engagement that has a long history: citizen enforcement actions, especially in the environmental context. The ability for citizens to sue for enforcement of environmental laws, in most cases with large pay-outs if successful, gives citizens great power, but requires a great deal of knowledge and sustained effort.

Institutionalizing Engagement at Each Stage of the Policy Continuum

As the concept of deliberate and robust engagement moves from the theoretical exercise to acceptance as an important element of 21st century democracy, it becomes essential to address how these practices can be incorporated into existing practices by policymaking actors across the continuum.

Just as the APA requires (under most circumstances) that federal agencies allow the public to submit written comments on proposed regulations, it is reasonable to expect that legislation in the near future will contain provisions directing the agency in question to undertake a participatory process that is more inclusive and incorporates “deliberative wave” principles. It is also likely that the process employed by the Natural Resource Committee for the drafting of its Environmental Justice for All Act will be replicated in some form by other committees that wish to increase buy-in and raise the voices of affected communities.

What might statutory language look like that directs an agency (or another government entity) to undertake such public engagement? What would it take to authorize, fund, direct, and undertake a participatory process during the regulatory stage? It is likely that a new participatory mandate could fall under the umbrella of the APA, but other statutes, such as the Paperwork Reduction Act that governs how agencies can collect data, might need to be amended, as well. How can these issues be anticipated now to avoid conflicts in later implementation?

Legislative language would have to make sure that necessary structures and resources are in place so that the agency has the right kind of expertise to implement the engagement, the right kind of expertise to be able to use the data gained from engagement in policymaking decisions, and sufficient funding to implement engagement processes—whether that’s a series of deliberations across the country or more robust systems that can be used to process written comments. Agencies tasked with conducting robust engagement will need to consider the details of how to do so. Not only would they need to hire or train current employees to attain expertise, but they must also, ultimately, figure out how to use data that looks unlike what they are used to. Agencies must learn to use data that is not in the form of technocratic expertise received from the usual suspects.

NOAA has been working with such non-technocratic expertise for some time now. In 2017, NOAA’s Ecosystem Science and Management Working Group of the Science Advisory Board released a report addressing the use of indigenous ecological knowledge (IEK, sometimes known as traditional ecological knowledge) and the use of local ecological knowledge (LEK) in its policymaking decisions. IEK and LEK are types of knowledge held by place-based observers. The report details some of the difficulties of incorporating these types of knowledge into a regulatory system that is based on scientific data, even when the value of such data is highly valued. One difficulty presented is that of validating the IEK and LEK:

“Validation” is used in two ways regarding ILEK [IEK and LEK, combined]. First, validation can be used to mean the result of a review process akin to peer review in the scientific world. In other words, it means confirming that the documented information does in fact reflect what is known to ILEK holders in the area who are familiar with the topic in question. Second, validation can be used to mean confirmation of the information itself by other means, most commonly by scientific experts. This second sense is highly contentious, as it implies that ILEK is not “valid” unless and until it is confirmed by others.

Expanding engagement and becoming more inclusive broadens the voices heard, as well as the types of knowledge brought to the government—even beyond IEK and LEK. As more people, with diverse ways of knowing their world, are brought into policymaking at various steps, we—as a nation—will have to decide in what circumstances and how everyday, lived experience is useful as we attempt to find more just and equitable ways forward. It is a conversation that began long ago in activist circles, but finding solutions and balance points will take time, deliberation, and likely a few failed attempts.

“Agencies must learn to use data that is not in the form of technocratic expertise received from the usual suspects. ”

Anticipating Judicial Review of Participatory Processes

As the First Branch, Congressional procedures are largely out of reach of the federal judiciary. If members of Congress wish to engage more or differently with their constituents as part of the political or policymaking process, the courts will have little to say, with a few exceptions. The first exception is judicial review that draws on legislative intent. Courts often interpret records of debate, including bill drafts and speeches offered by legislators, to determine if the intent motivating the statute violates the U.S. Constitution. This idea — of creating a record of how the government decided upon the policy it enacted and that this record is then reviewable by a court in the course of a lawsuit — is fundamental to protecting individual rights.

Creating a record is also a crucial part of the policymaking process in the regulatory stage. Agencies are required to keep track of which advocacy groups they meet with while drafting regulations, to take (and make available to the public) notes from public meetings, and to release internal reports upon which agency decisions were made in the course of rulemaking. This record, too, is reviewable by courts. Part of this record is how notice and comment rulemaking was carried out and whether it offered a meaningful opportunity for the public to comment. As noted by the United States District Court for the District of South Carolina, “An illusory opportunity to comment is no opportunity at all” (South Carolina Coastal Conservation League v. Pruitt, 318 F. Supp. 3d 959, 966 (D.S.C. 2018)). The court found that the comment period in question was too short to give the public adequate time to consider the proposed draft and submit comment on it.

The record is also important in determining whether the resulting regulation was “arbitrary and capricious,” a term of art that, for our purposes here, means: was the decision supported by the record. Regulatory policy usually relies on technocratic ways of knowing the world. Standards such as whether an agency policy is arbitrary or capricious, or what qualifies as expert evidence upon which decisions are based, have developed in the context of technocratic expertise, not the language and experiences of lay people. Gatekeepers who decide what qualifies as “expertise” necessarily—and with good reason—follow these standards. How might a court interpret policy decisions that are made with significant input of non-technocratic expertise? The Ecosystem Science and Management Working Group report notes that validation of IELK occurred “in the context of meeting the standards of courtroom litigation” (8). Would the incorporation of such expertise run the risk of seeming arbitrary in a justice system so heavily influenced by scientific standards?

And yet, environmental and natural resource agencies have been collaborating with holders of IEK and LEK. The U.S. Forest Service, for example, has had some success working with family forest owners on issues of biodiversity. “[F]amily forest owners are aware of aspects of biodiversity—including species diversity, structural diversity, ecological time scales, and landscape context—and may be predisposed to developing local knowledge” (2008, 21) but there are “[f]ew prominent examples of cooperation between family forest owners, scientists, and other land managers exist to serve as models for integrating their LEK in biodiversity conservation efforts” (24). Note that collaboration with holders of IEK and LEK tends to occur earlier in the policy-making process, not necessarily as the agency is preparing a regulation; perhaps this timing points one way forward for bringing in more voices to policymaking.

Evaluating the Success of and Refining Participatory Processes

A final element of consideration loops back to the initial one: Why do we want more engagement? Having a specific, identifiable goal is the first step to being able to measure whether the goal has been reached. The OMB’s report to the White House, “Study to Identify Methods to Assess Equity: Report to the President,” offers a working starting place of methods of inclusion and assessment of equity gathered from across the country. Some examples of collected methods and tools include microsimulations to identify potential policy outcomes on specific communities, the Urban Institute’s Spatial Equity Tool to map resource disparities in cities, and the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Community-Based Participatory Research Program (CBPR), which “supports collaborative interventions that involve scientific researchers and community members to address diseases and conditions disproportionately affecting health disparity populations” (NIH 2018).

Not all of the methods, tools, and approaches collected in the OMB report are interchangeable, nor are all appropriate for each step of policymaking. Notably, the report includes not only processes and methods for undertaking more inclusive engagement, but identifies potential outcomes. For example, “When principles of engagement and participation are folded into substantive policy design, the number of choices and trade-offs may increase. Experts in community-engaged methods stress that navigating decision points like these with respect and recognition of diverse community perspectives yields more robust policies and programs and delivers better outcomes” (OMB). In other words, deeper engagement requires patience to work through multiple viewpoints, concerns, and considerations. This, like setting the goals of engagement to begin with, is necessarily a messy process. The after-action analysis that the government undertakes after the policy is created, implemented, enforced, assessed, is crucial to the development of an organizational culture that develops and cultivates such patience.

“there are now new tools and techniques—from new technologies, to new modes of organizing, to new innovations in institutional design—that can be repurposed and expanded to create a new infrastructure of democratic practice”

Conclusion

For too long, the government has drawn only from voices empowered by class, race, and education to speak in technocratic languages to influence policymaking; stakeholders have become the public to which government answers. However, as Sabeel Rahman and Hollie Russon Gilman note, “there are now new tools and techniques--from new technologies, to new modes of organizing, to new innovations in institutional design--that can be repurposed and expanded to create a new infrastructure of democratic practice.” Engagement for the 21st century can make use of these new tools and techniques to deepen and make more inclusive the relationships between the public and the government, strengthening our democratic institutions, infrastructure, norms, and practice.

“Engagement for the 21st century can make use of these new tools and techniques to deepen and make more inclusive the relationships between the public and the government, strengthening our democratic institutions, infrastructure, norms, and practice.”