David vs. Goliath, But They're the Same Person

The 2x2 matrix that explains why our politics sucks

BY ANNE MEEKER

I didn’t end up writing about it at the time, but last fall, I was absolutely glued to Adam Bonica’s work at On Data and Democracy looking at the network of fundraising and advertising entities that make up an unhealthy portion of the Democratic party’s campaign infrastructure. It’s a deeply frustrating/fascinating body of work, and a familiar one — not least because the Republican party went through its own similar crisis of outreach tactics a few years ago.

But looking at the raw numbers involved in this ecosystem, something struck me that I’ve been thinking about ever since.

Per OpenSecrets, the amount of money spent in Congressional elections in 2024 was $9.5 billion, in addition to the $5.3 billion in the presidential race. By contrast, the 2026 Legislative Branch Appropriations Bill (House and Senate) includes $1.5 billion for the funding for individual legislators’ offices — which is the only funding available for Congress to spend on contacting constituents as part of its official or governing responsibilities.

In other words, Members of Congress only have 15% of what’s spent on getting them elected to do the job they’re elected for. As of this early point in the 2026 Congressional campaign cycle, at least 67 candidates for the House and 40 candidates for the Senate have already raised more money for their campaigns than they will have available to run their offices if elected.

This newsletter focuses on that official side of engagement and interactions between legislators and the people they represent. But, as we enter another Congressional campaign year, we can’t not address the absolutely massive imbalance between campaign and official/governing spending to reach the American people, and what that means for our system of government.

Rep vs. Candidate and Constituent vs. Voter

Let’s talk both theory and practice for a second.

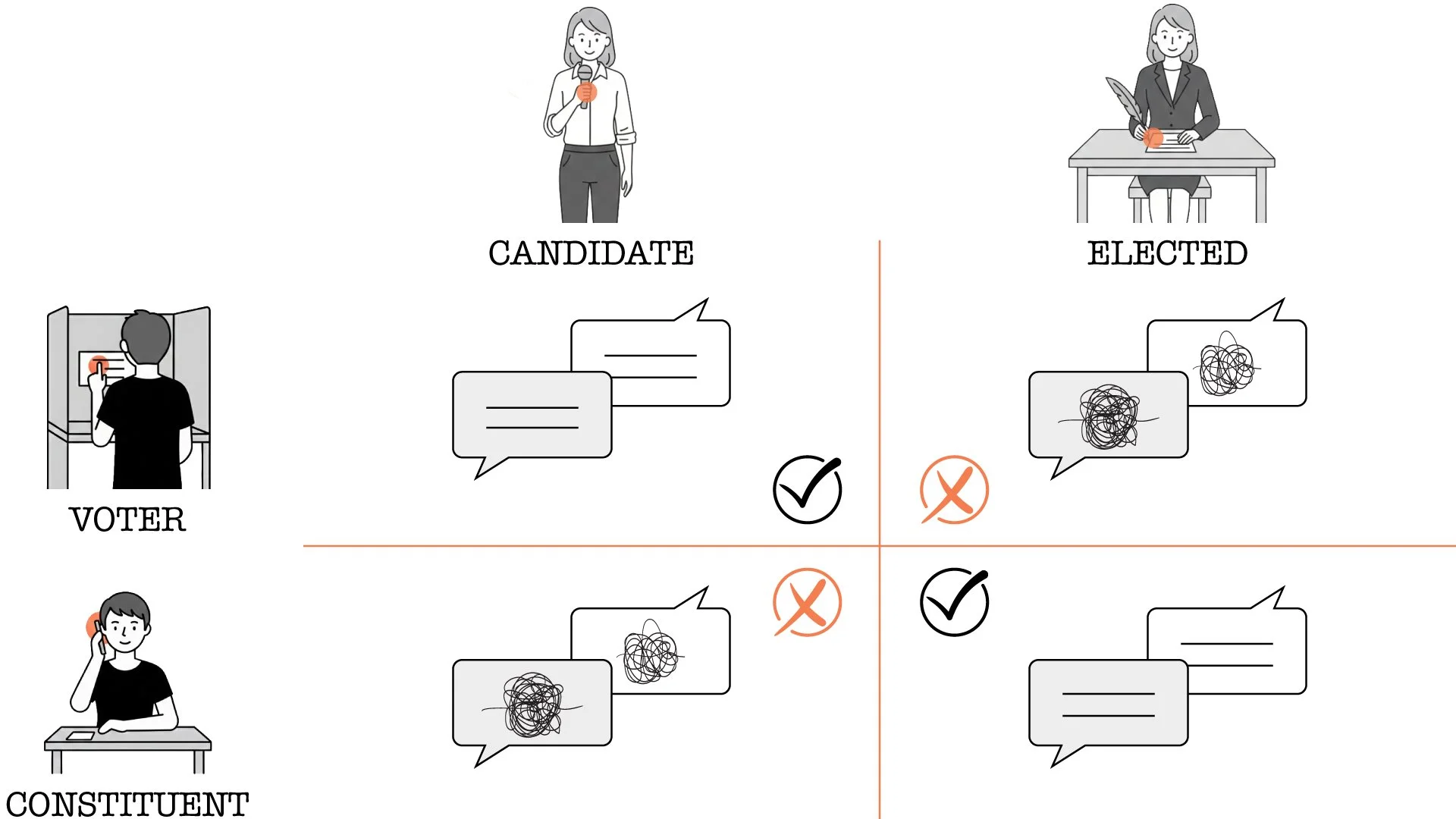

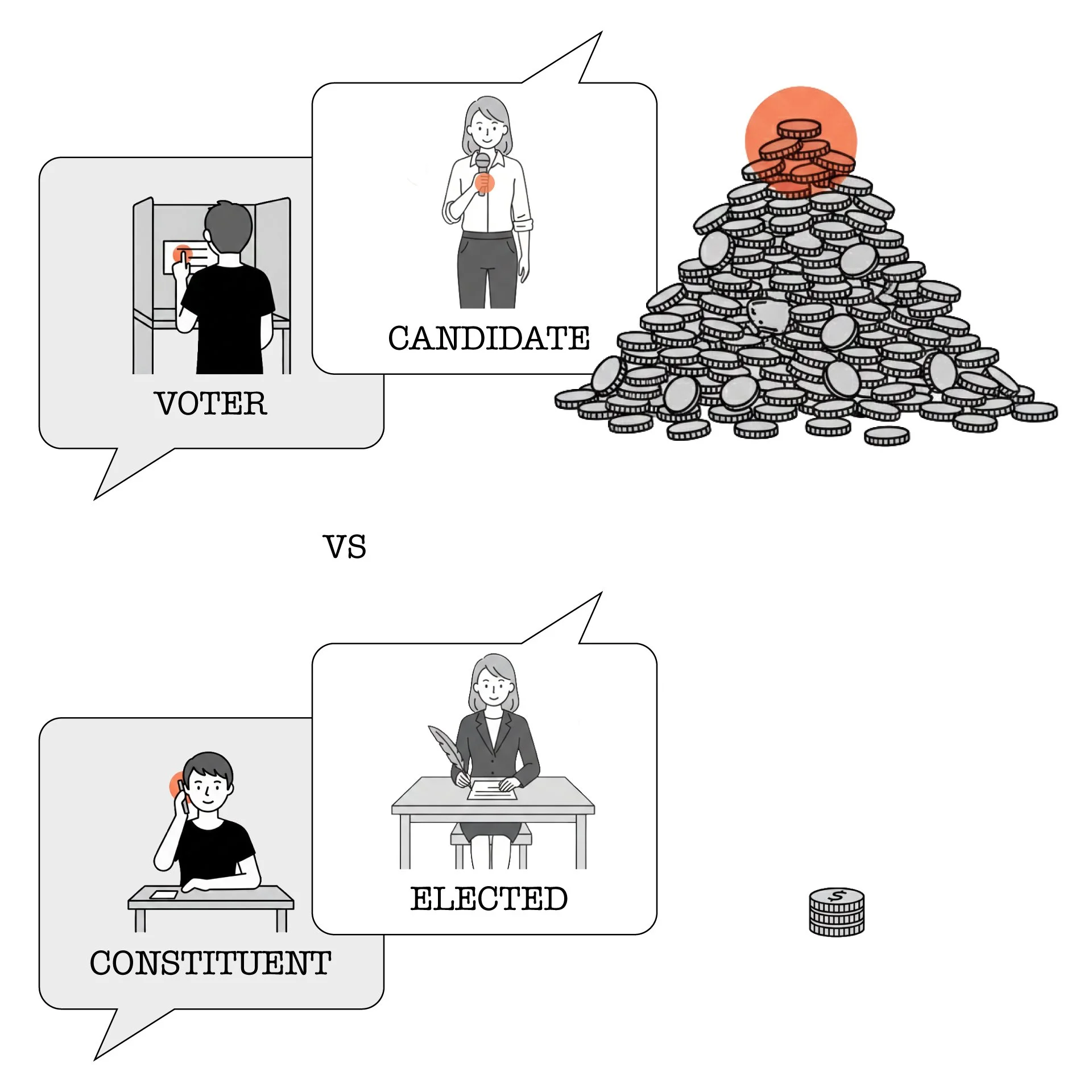

Our political system and the system of laws, regulations, and norms designed to prevent corruption create a 2x2 matrix that governs how people and politicians interact at any given time:

On one side, we have two potential roles for the politician: as “candidate,” seeking public office, and as “elected,” having been chosen by the voters for that office.

On the other axis, we have two corresponding roles for the public: “constituent” — the group of people represented by a specific elected official, including non-citizen residents — and “citizen/voter” — the group of people with political power to participate in elections.

To be clear, this is all kabuki theater, or Michael Scott declaring bankruptcy: it’s the same group of elected officials, and on some level they get to decide when they are performing each separate role. But on the candidate/elected side, it’s a legal distinction with practical implications, and the very real possibility of civil and criminal penalties for playing the wrong role at the wrong time.

Those penalties come down to how money is spent. The basic concept is simple: campaign dollars for campaign purposes, and official dollars for official purposes, and neither for personal use. GovTrack’s database of legislator misconduct is full of examples of Members from both sides of the aisle landing afoul of these rules, including misusing official funds for campaign purposes, or improperly steering official funds to campaign contributors, using campaign funds for personal expenses like gift cards and club memberships, or requiring official staff to perform personal errands.

What a great excuse for us to look at former Rep. Aaron Schock’s [R, IL] “Downton Abbey” themed office, for which he repaid $40,000 in improperly-spent official funds.

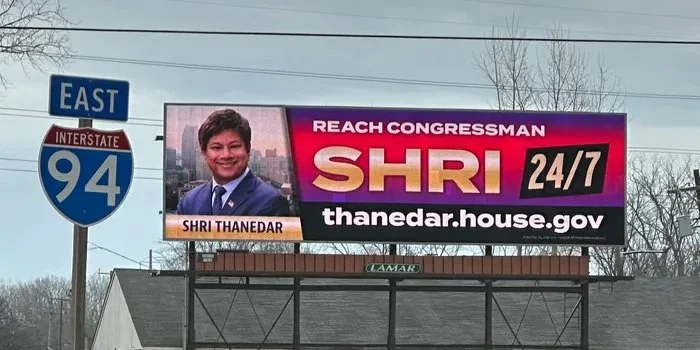

There are grey areas for sure, and these rules are frequently litigated, with perennial controversies over whether the use of official funds for something like — say — a billboard with the Member’s face on it, advertising constituent services, is too close to campaigning.¹

To be clear, I love advertising for constituent services, but it can be controversial.

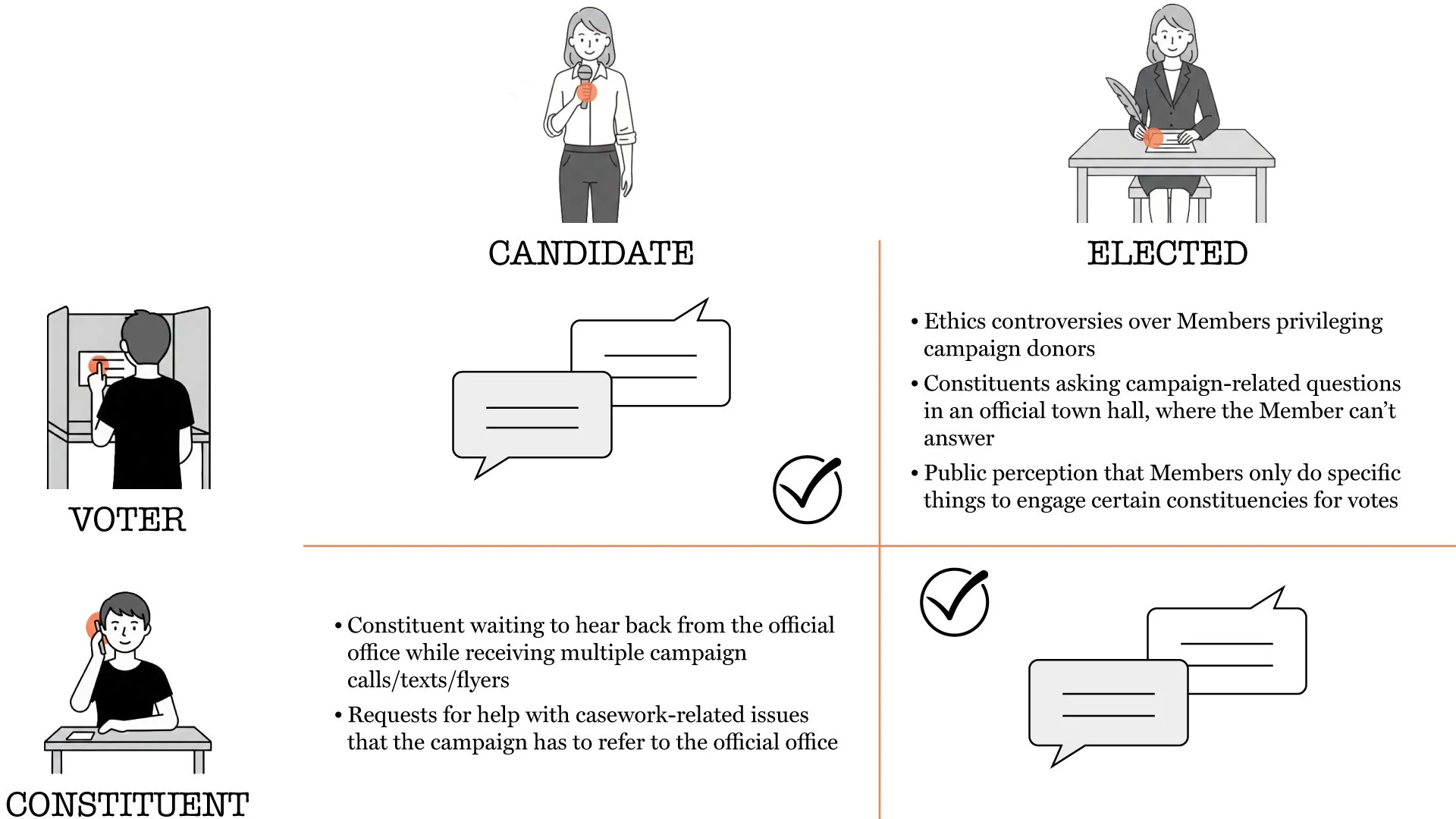

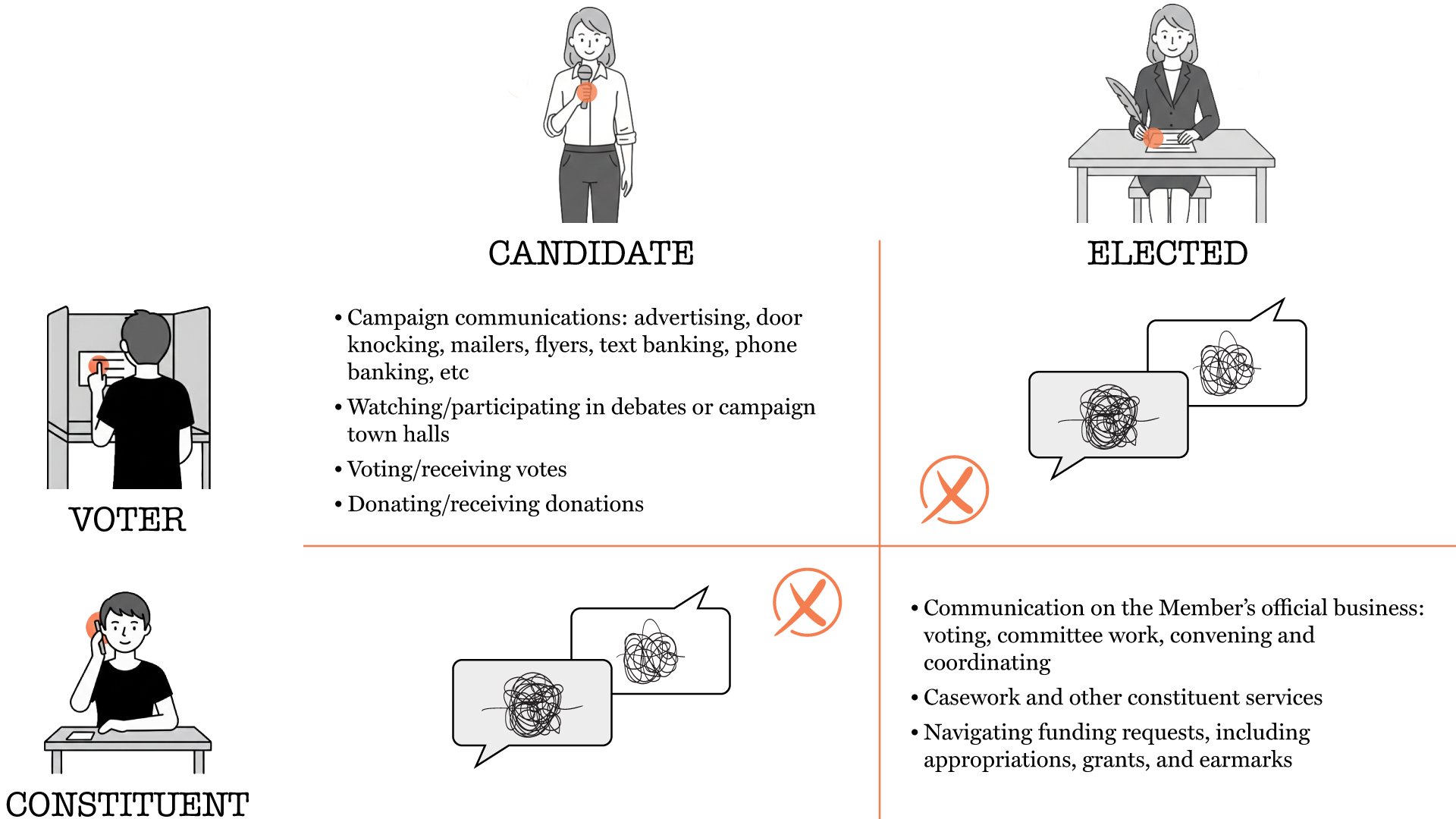

When it comes to how people and politicians interact within these roles, that situational role-switching gets complicated, and creates plenty of opportunities for misunderstandings and awkwardness. You can already see how interactions in the top left and bottom right quadrants are clear and healthy and make sense — but the ones in the bottom left and top right get weird. We may talk more about those weirdnesses some other time.

Both halves of this are critical to a healthy and functioning system of representative democracy: the campaign interactions where constituents and Members choose an agenda, and the governing work of representation. But the scale available to both sides is vastly unequal.

The average Members’ Representational Allowance (MRA), or the budget that each individual House Member gets to carry out their official duties — including personnel, office expenses, travel to the district, and mail for Members of the House — is $1,928,107. The Senate is a slightly more complex calculation, but the average Senator’s budget (SOPOEA) is $3,738,775.

On average, an incumbent member of the House will raise $2.1 million for their reelection; a freshman Member will raise $2.4 million, and an incumbent member in a “toss-up” district will raise $7.9 million — or almost four times the amount of money they will have to govern if they win. That is also not counting the amount of campaign-season spending beyond campaigns themselves from PACs, Super PACs, and advocacy groups.

And it’s not even an apples-to-apples comparison: unlike MRA money that has to go toward lots of different activities and needs, the primary purpose of campaign spending, no matter who it’s coming from, is to contact voters.

Campaign spending on activities to reach Americans vastly, enormously, exorbitantly, tremendously, gigantically outweighs the official-side spending to reach the same people.

Not to scale, but very much adjusted to vibes.

So then the real problem of the kabuki theater/role-playing is that only one side knows that it’s playing two separate roles.

Most Americans are not savvy enough to the complicated rules of campaign finance and Congressional ethics to understand and recognize that distinction. This means that for the vast majority of people, the constituent vs. voter and candidate vs. elected dynamic is a distinction without a difference.

It’s this imbalance that creates the perception that politicians only reach out when they want your vote — not to ask for your opinion, share what they’re doing on your behalf, help you/your kids understand your government, or provide direct services like casework, academy nominations, grant support, etc., but to lie to you about a fake matching opportunity, ask you to sign a useless petition, and beg for 15 bucks.

When you’ve gotten a million campaign contacts but call your Member’s office and can’t get through to anyone to help with an urgent issue, or get a generic form letter in response to your considered email, you don’t see a scrappy resource-constrained Member of Congress doing their best to reach hundreds of thousands of constituents with limited resources — you see a Member that’s only interested in extracting funds and votes from their constituents, not serving them.

The Campaign vs. Governing Pacing Problem

In our work at POPVOX Foundation, our central organizing principle is helping legislatures address the “pacing problem,” or the growing gap between the rate of technological and societal change, and the ability of legislatures to keep pace.

The race between campaigns and elected/governing institutions for public attention is its own version of that pacing problem. Beyond the sheer scale of contacts between campaigns and governing operations, that resource gap also means that campaigns can (and must) experiment with new and technologically savvier methods of communication in a way that is less available to governing institutions.

In the last few election cycles, campaigns have experimented with…

Discord chatbots to reach young Americans with information about voter registration, voting reminders, polling place locations, etc.

Sentiment analysis tools to process voter input from thousands of hours of recorded phone calls

Precision voter identification and ad targeting based on the same consumer data used in retail marketing

Automated campaign-internal workflows, triggering next steps based on input from volunteers

Relational organizing tools, mapping, modeling, and utilizing real-life social networks to facilitate trust-based outreach

Do I think we need to address the scale of money in politics? Yes, absolutely, although it is well above my pay grade and out of scope for this newsletter to suggest what that might look like.

But I think that the more interesting question for Congress and for civil society is to ask what it might look like to have the same level of resources, creativity, and drive to innovate on the official side as on the campaign side. Instead of turning down the campaign noise and scaling back the top left quadrant of that matrix, what if we turned up the volume and exploded the bottom right corner of the matrix to start to match? And unlike campaign finance reform, these are changes that can happen without a constitutional amendment or a Supreme Court reversal.

This imbalance is the backdrop for everything we cover here — every franking reform, every CRM upgrade, every experiment in constituent engagement is an attempt to give David a slightly better slingshot. If we get this right, maybe the next generation of constituents won’t assume that every contact from their Member is an ask. Until then, the loudest voice in American democracy will keep being the one asking for $15.

¹ It’s worth noting as well that the membrane is slightly more porous in the other direction, with some limited freedom to use campaign funds for activities that get close to official business (like paying for the Member’s travel, or for portions of a staff retreat).

Voice/Mail is a Substack newsletter about how people and their governments talk to each other. Learn more and subscribe at voicemailgov.substack.com.