How Legislative Office Structure Creates Bad Politics

Why Listening to Constituents is at the Bottom of the Priority

BY ANNE MEEKER

Jennifer Pahlka has a piece on her wonderful Substack, Eating Policy, elevating two examples of being a good politician:

the mayor of San Jose’s response to a constituent’s tweet about overly-burdensome regulations for planning applications to create affordable housing, and

Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez’s [D, WA] work to address regulations preventing daycare center employees from peeling a banana without a dedicated prep sink.

As Pahlka put it:

“The real triumph here is that [they] engaged in this issue in the first place. So many politicians would consider this kind of administrative detail unworthy of their attention.”

To Pahlka’s analysis (which, to be clear, is spot on as always), the critical element that separates a good politician from someone just interested in grandstanding about the issues of the day is political leadership. The vision and drive to tackle something as pervasive and nebulous as culture.

Pulling a “yes, and” here — I think there is a missing structural and cultural element on the elected side as well.

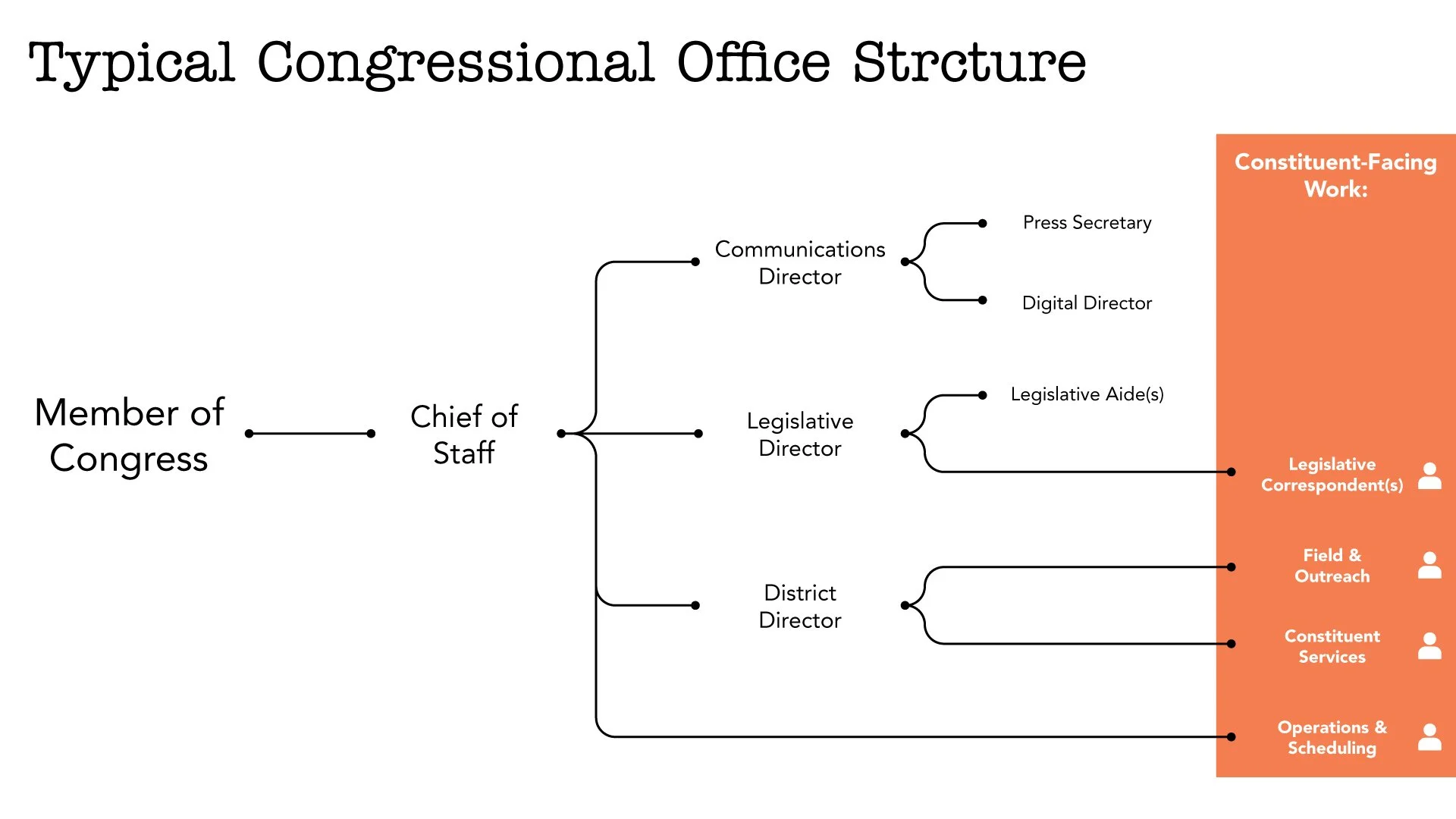

Let’s start with the structure. Elected officials absolutely rely on staff, and the ability to recruit, manage, and retain excellent staff is one of the key things setting great politicians apart from mediocre ones. But when it comes to actually divvying up labor between staff members, there is a pretty set-in-stone model for staffing an office.

In that internal hierarchy of the vast majority of legislative offices, constituent-facing work is firmly at the bottom.

For young, idealistic, rising Congressional staffers, the reward for moving up in the hierarchy of political jobs is talking to the public less: the legislative correspondent who spends ninety percent of their time handling the mail and phones wants to be the legislative aide who might spend ten percent. The staff assistant managing the intern program to keep the phones answered wants to be the field representative who manages relationships with “stakeholders” — the elected officials, business leaders, and other VIPs.

And, closest to my heart and also to these examples, the caseworker or constituent services aide, who’s explicitly tasked with working one-on-one with constituents to identify and solve this exact type of administrative snafu, is stuck pigeonholed outside of the main lane of the policy process.

That structure creates and reinforces culture in a few big ways.

First of all, the people talking directly to constituents have the least authority in the office — they have the least direct contact with the Member or the Chief of Staff, and the least pull to decide what makes it onto the legislative agenda or the communications agenda.

They’re also likely to be the most junior, with the least experience and policy context to sort through massive amounts of incoming information (all stacked with its own emotional valence) to identify the needles in the straw.

And, obviously, there are external factors: talking to the public can absolutely suck. People are angry in general, and especially angry with Congress. Experienced caseworkers tell me that the levels of patience and grace constituents are willing to extend to Member office teams have never been lower. I have zero time or tolerance for commentators who dismiss the very real, present risk of political violence directed at Members and staff.

All of this together creates the perfect environment for some anti-public sentiment that can be pretty toxic in the wrong offices. The same way that overloaded ER staff will start to label repeat patients as “medication-seeking” and overlook actual pain, elected offices facing burnout and overload will also start to engage from the starting assumption that constituents are attention-seeking, paranoid conspiracists, or that the problems they call to complain about are user error instead of structural or programmatic issues — not worth taking the time to investigate.

But even more perniciously, even in offices that avoid this type of toxic anti-public culture, we are also seeing the long-term failure of a customer-service approach to constituent engagement. Over the last several decades, Congressional offices have been encouraged, internally and externally, to adopt practices, language, and understandings of success from the business world, treating constituents as “customers.” It’s a very metrics-based approach, where the goal is numbers:

how many cases did we close?

How many letters and phone calls did we answer?

How fast did we answer them?

What’s our net promoter score?

But the customer service approach treats symptoms, not root causes. A constituent calls about a delayed passport, gets helped with their individual case, but the office never flags the pattern that could inform oversight of State Department processing delays.

That legislative hierarchy exists for a reason: you obviously do need some specialization and career pathways. However, the issue is the way that hierarchy creates and reinforces a culture that prevents actionable constituent insights from making their way up the chain.

So: if you want politicians who are willing to grapple with the culture of agencies and runaway proceduralism, you need politicians that are willing to take some risks and create an internal culture where constituents are treated as experts in their own lives and partners in the business of governing, and constituent input is integrated into every level of an office’s work.

For those of us on the outside who dearly want to see this leadership, I think there are a few concrete things that will help — I’ll likely dig into these in more depth later, but off the top of my head:

Support offices experimenting with new work structures.

That hierarchy is the norm, not rule, but mixing it up requires extra work. Civil society can help with resources, training, and staff recruitment — or help traditional offices foster stronger relationships between district and DC staff.

Develop training to identify and elevate constituent-facing expertise.

I was inspired by my recent conversation with Chelsea Mauldin from the Public Policy Lab on approaching constituent engagement as qualitative research. We need formal training for teams on how to solicit, capture, and utilize deep learning from constituents, breaking out of the customer service mold.

Build relationships with constituent-facing staff.

Policy organizations should develop contacts with caseworkers and field representatives, not just policy staff. External validation of their expertise helps shift internal culture.

Support vendor ecosystem competition.

The Congressional tech approval process privileges existing vendors who reinforce the customer service model. More openness (with appropriate security) could expand the toolbox for creative constituent engagement that solicits this type of actionable information.

Cheerlead relentlessly.

To reinforce Pahlka's point — when politicians do engage with administrative details that affect real people's lives, we need to celebrate that as the essential democratic work it is.

Check your voicemail

There is SO MUCH HAPPENING in the constituent engagement world right now. Here’s a quick snapshot.

AI and Engagement

This is crazy: results of a simulation of 1,000 real, unique humans using AI agents and comparing the agents’ responses against the human responses showed 85% accuracy at replicating the real humans’ responses. This…opens up some possibilities.

Personally, I’ll be attending every workshop in this series on AI for public engagement from the wonderful folks at the Burnes Center, and you should join me.

Speaking of, DC is wrapping up a pilot public consultation using deliberation.io, an AI tool to structure public listening sessions.

NYT is reliably quite doom-and-gloom on AI and democracy, but this is nonetheless a good roundup of examples of AI being used to influence parliamentary elections around the world.

Civics and Education

If you are an outreach staffer for a Member of Congress…It is probably time to start thinking about what your office will do next summer around the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (don’t shoot the messenger!). To get you started, here is a cool structure for a Declaration of Independence book club from the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello. Maybe something to share with schools and summer camps?

Speaking of civics: I’m still thinking about the mock Convention Bill and Ed from Convention of States talked about a few months ago, and this new report on the state of experiential civics learning extends some of those lessons.

We’ve talked about youth competitions and contests for constituent engagement before — the White House is spinning up a new version with the Presidential Artificial Intelligence Challenge.

Nuts and Bolts of Engagement

Franking nerd questions moment: who maintains control of a lawmaker’s social media accounts after they pass away while in office?

To follow my convo with Chelsea Mauldin last week — this is a very cool perspective on what it would look like to incorporate public input at the tech procurement stage of policy implementation. Give people options for what dratted interfaces they’ll need to use to access vital gov information and services!

This is twice this year now that the Ohio Congressional delegation has found itself facing constituent blowback over a glitch that I am pretty sure is a CRM issue in both cases.

The Guardian covered the dramatic increase in threats to Members and staff at all levels of government, and how lawmakers are balancing accessibility with safety.

A moment to be grateful for free speech protections in the US: a Kenyan software developer describes her imprisonment over a tool to help Kenyan citizens submit public comment on the government’s revenue and tax proposals.

Social Security’s recent reply-all email (to…everyone?) about the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act sparked some controversy. It’s not the first time an agency has gotten in trouble for “propagandizing.”

From across the pond: the UK Parliament published an interesting overview of the relationship between parliamentary constituent engagement and public trust.