The People Will Stand and Deliver

If you’re struggling to find faith in American politics and the future of Congress right now, tune in

BY ANNE MEEKER

When you tell people you run a Substack-slash-research-project on the present and future of constituent engagement, you get one of two things: a blank stare, or a question about either mail or town halls.

I can’t blame them: local news about individual Members of Congress this year has been very town-hall centric — unsurprising, considering that Members have hosted more town halls this year than almost any year prior. We’ve seen Members on both sides of the aisle come under criticism for canceling or not hosting town halls. Members who have hosted town halls have frequently seen them disrupted, or canceled them entirely out of concern for their safety and that of their constituents and staff.

With such sturm und drang over the town hall through generations of politics, you’d think that town halls might slide off the map entirely, and be replaced by more controllable, smaller, asynchronous methods of engagement. But the town hall endures, through multiple incarnations and models and forms, even when those forms exist only in our nostalgic imaginations.

“Not this guy again…”

The running theme of this newsletter is that the landscape of legislator-constituent contact is deeper, richer, and weirder than it seems from the surface — and the deeper we get into town halls, the more it’s clear that this is not only true of the variety of methods of engagement, but also within specific methods of engagement as well.

Town halls represent many of the challenges and opportunities of constituent engagement in microcosm. Large ratios of constituents to representatives mean there is an imperative to find at-scale methods of communication. The agency of individual Members of Congress on legislation is sharply curtailed. New technologies make new things possible, but strong traditions make old forms sticky. Polarization and mounting political frustrations create genuine security concerns, but also a strong desire from “ordinary” people to be part of the solution.

Tensions like these drive creativity, and that’s where the exciting stuff happens.

Over the next few weeks, this newsletter will feature several interviews with smart people who are helping move town halls forward: practitioners, researchers, entrepreneurs, and former staffers asking questions about what town halls are and should be for. These are folks thinking about town halls as information-gathering and habits of civic participation, as methods of communication and negotiating a shared agenda; about how do you get new people in the room, and how do you create an experience they’ll want to return to; about how Members and constituents can balance safety in strange times with the genuinely transformative effects of participating in your own democracy.

So let’s kick it off with a big-picture conversation with two of the people who have been most instrumental in re-envisioning what town halls can be: Professor Michael Neblo and Amy Lee of the Ohio State University’s Institute for Democratic Engagement and Accountability (IDEA).

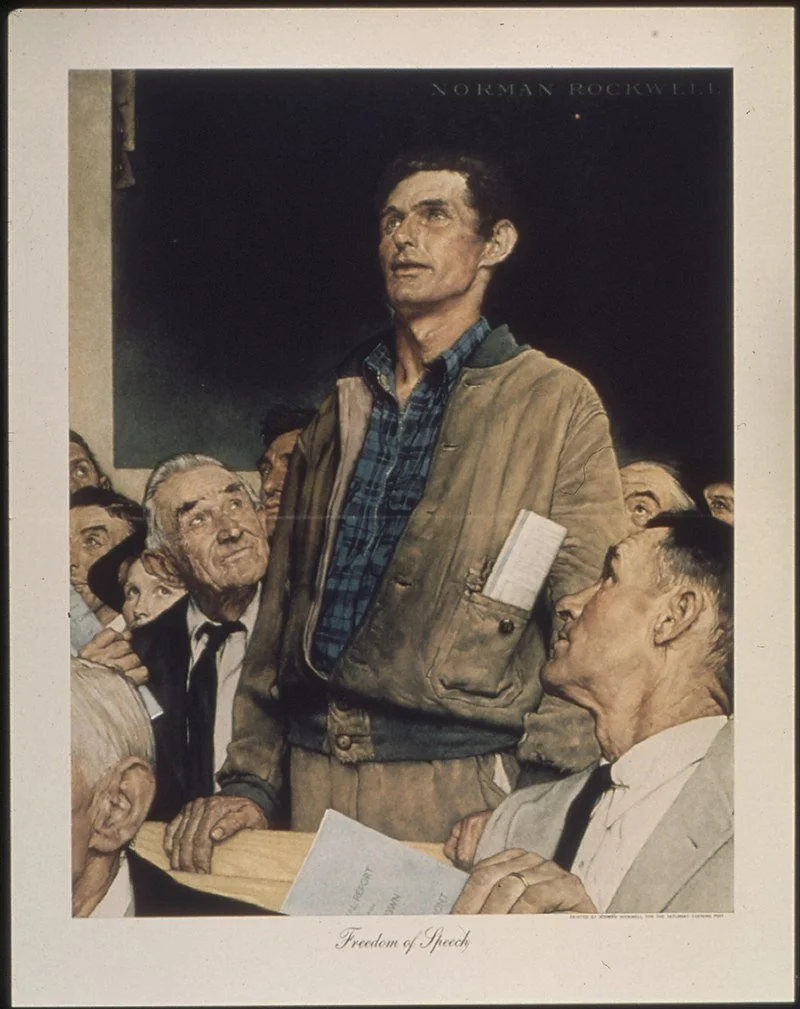

As you’ll hear in this conversation, Michael and Amy come into the conversation with over fifteen years of data on town halls that break the “traditional” mold that comes to mind with the Norman Rockwell painting and the media coverage of disruptions and f-bombs and security threats — and, from those fifteen years of work, an incredible faith in the power and potential of constituents and legislators working together. There is so much to unpack in this conversation, but in particular, one finding stands out to me: how individual Members, by inviting constituents to participate, can all by themselves play a significant role in reducing affective polarization.

And, for all of us working in the para-Congress space: don’t miss Michael’s pep talk at the end about how faith in our institutions is sometimes rewarded beyond our wildest dreams.

Michael Neblo‘s research focuses on deliberative democracy and political psychology. His most recent book, Politics with the People: Building a Directly Representative Democracy (Cambridge University Press, 2018), develops and tests a new model connecting citizens and elected officials to improve representative government. His work has appeared in leading journals including Science, The American Political Science Review, and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He holds a PhD in political science from the University of Chicago and directs Ohio State’s Institute for Democratic Engagement and Accountability (IDEA) and its initiative Connecting to Congress. He has received awards and grants from the Carnegie Corporation, the Democracy Fund, the National Science Foundation, and other major foundations to design and study Deliberative Town Halls with Members of Congress.

Amy Lee is the Associate Director of the Institute for Democratic Engagement & Accountability. Her focus is developing and testing practical innovations to make democracy both more participatory and also more deliberative. Previously, Amy was a program officer for eight years with the Kettering Foundation, a research foundation that studies deliberative democracy, particularly democratic decision making. At Kettering, she led the development of the foundation’s platform for online deliberative forums, Common Ground for Action, a transparent, visually engaging environment for deliberative decision making. She also led the training of its network of users and directed research evaluating its effectiveness. The platform is now being used throughout the US by communities, professional organizations, educators and policymakers, including members of Congress. Amy was also a 2018 Marshall Memorial Fellow, participating in the German Marshall Fund’s immersive program for emerging leaders focusing on the transatlantic engagement and collaboration.

Transcript

This transcript has been edited for clarity and may differ slightly from the audio recording.

Anne Meeker: Amy and Michael, it is so good to see you. Thank you so much for joining us. I feel like I have to give a little bit of backstory here, because in many ways, you two are the reason that I am in my current role and the reason that this Substack exists. For background background, after I left my role, working for a Member of Congress, I had the extraordinary pleasure to be a Fellow with the (the) Ohio State University’s Institute for Democratic Engagement Accountability [IDEA], where I got to work closely with Amy and Michael.

And that was my moment of transitioning from “staffer” — this is how you exist in the way things are — to whatever I am now — let’s think about how this goes from here and how this changes. So I am just incredibly grateful to you both for that whole experience, and then definitely for you taking the time to chat today.

Can I have you two just give a super quick intro background on your work and, and IDEA?

Michael Neblo: Sure. Okay. So, I am a political scientist at the Ohio State University, but I spread out across the university a fair bit. I have joint appointments in Poli Sci, in communications and public affairs, and I direct and founded the Institute for Democratic Engagement and Accountability. In the earlier part of my career, I was more of an academic academic: just went into the office, read, wrote, and taught. As I got tenure and time moved on, I realized that I had more project ideas than I’d be able to execute before I was going to retire. So I made a conscious decision to start orienting my research towards high-impact research that’s teed up to improve democracy. The idea is not to give up on basic research, but to lessen the tension between [academic and] applied research that can speak to what practitioners care about and actually help heal our politics — doing so in a way that preserves the real advantage of the academy, which is rigorous empirical and theoretical backing for that work.

I coauthored a book called Politics with the People, Building a Directly Representative Democracy with my colleagues, Kevin Esterling and David Lazer, where we articulated this vision of democratic reform that was different than a lot of the going alternatives, which were trying to work around representative democracy. Our approach was to try to make representative democracy work more like the way our civics textbooks taught us it should work. In particular, overcoming or lessening the challenge that elected officials face in real and robust consultation with their constituents. James Madison’s first First Amendment failed. The first First Amendment when it was proposed was from Madison to cap the number of residents in a congressional district. Instead, in 1913, Congress capped the number of representatives. And the upshot is the average member now represents 280 times the number of voters — eligible voters — that Madison thought was the upper limit for real consultation to steer between mob rule and aristocracy.

I think that’s at the heart of a lot of the crisis of American democracy and global democracy. Part of what we try to do with Deliberative Town Halls is lessen that tension by making it easy for people to participate through technology, and through sortition and randomization and random samples to draw in the full range of people — now that it’s not just propertied white men who get to vote.

Amy Lee: And I’m Amy Lee, I’m now the associate director of IDEA. And before I came to IDEA, I was actually working at the Kettering Foundation as a program officer, and getting to work with and support lots of really cool organizations that were trying to do deliberation, primarily kind of horizontal citizen-to-citizen deliberation. And it was super inspiring work — but I wasn’t necessarily seeing the impact on policymaking and the virtuous cycle of increased public trust and everything, all the other impacts that you’d really want to see, beyond just the impacts on citizens themselves. So when I read Michael’s book and I had been introduced to him through the foundation before, I was like — oh, this is what we need to do.

So I told Michael, “I would like you to hire me.” And I came and joined IDEA and we rebooted the Connecting the Congress initiative, and did over two dozen Deliberative Town Halls in the next couple of years for 17 Members of Congress. We learned a lot about what could be updated from the original round of experiments into a later, post-2016, much more polarized, much more tech-fragmented society, and were able to find some really interesting things that most of it actually did hold up. There had been some lessening of some of the gains of it, but overall, it still did amazing things for increasing trust and approval and the participating members in the institutions. It had impact on policy, as we were able to find out from some of our interviews with Members of Congress. So we really were able to find out a lot of really interesting things, including a new finding that I think Michael will be able to tell you about.

Michael, why don’t you actually explain very briefly how a Deliberative Town Hall actually works and explain how the congressional committee, how the select committee one worked, and then it will lead right into the finding.

Michael Neblo: Okay. So the idea behind Deliberative Town Halls really grew out of watching standard town halls more or less implode during the Obamacare debates, where both MoveOn.org and the Tea Party in their manuals had instructions for their members on how to disrupt standard town halls and to embarrass the elected officials on the other side.

Unsurprisingly, the response was for a lot of elected officials to either withdraw and not do as many town halls, or for staff to try to control them closely so that they didn’t get ambushed. Which isn’t great, but it’s certainly understandable under the circumstances. And the upshot of it was what was already, frankly, mostly talking points and venting became something worse than talking points and venting — not just not valuable, I think actively harmful. It was damaging public discourse.

And so we paused and said, can we do something like this that’s in the spirit of what town halls were supposed to do, but do it better and make it robust to these attempts to crash them? And draw Members back in with a credible claim of being able to do something better, and similarly to draw citizens back in—the ones who aren’t interested in throwing bombs or torching their Member of Congress, who just want to have their voices heard or hear from their elected officials about why they represented them the way that they did, and to talk to their fellow citizens about it.

So the idea behind a Deliberative Town Hall is like a standard town hall, but with a few really key differences. One is that we pull random samples of a constituency and affirmatively invite them and work very hard to make them inclusive and accessible to anybody who wants to participate. Part of the problem with standard town halls is that if they’re held in suburbs during the day, then it’s retired people or highly motivated people or people who can easily get childcare, or don’t have children or their children are out of the nest, who can attend. And so you get these very highly skewed groups of people. They’re great citizens — I’m not criticizing them. They’re showing up for their democracy. It’s just that collectively, the structural features lead to very extreme, non-representative signals that are being given to the elected officials. And they need to hear from those people, but they also need to hear from the people that aren’t speaking up unless they’re asked and invited affirmatively. And so that’s what we focused on.

And we were very successful and super excited to learn that it was exactly the people who weren’t voting and weren’t working on campaigns or donating or being involved in any way — they were not apathetic. They were frustrated and thought such participation was a waste of their time. And when their Members signaled to them, “I really want to hear what you have to say. How does seven on Tuesday night work?” they were lining up to do it.

The second big difference is that we focused on one issue at a time. And the idea there is that you can’t sustain talking points for 60 or 90 minutes. Talking points are designed to be quick hitting and move on. And so both from the point of view of the constituents trying to make a point in some bomb-throwing way and the elected officials just giving the quick standard response, not much progress gets made on that. And so by focusing on a specific issue, we’re able to go in much more depth and to ensure that the members are really articulating their views in a more developed and nuanced way and that the constituents have a chance to engage at that level.

Now, one obvious problem with that approach is that the average citizen isn’t necessarily particularly well informed around a range of issues. And we’re back to the situation where it’s really just the most intense people if we just rely on the folks who already care about that issue. So one of the things that we do to help that problem is prepare background materials — short, 2 to 4 pages, but drawn from highly reliable bipartisan sources and scaled to a ninth grade reading level — to bring everybody up onto the same page on the facts and to provide them with the basic information that they need to be able to engage meaningfully.

And we had tremendous success. The original ones were largely with individual Members of Congress and samples of their constituents. And since then we’ve branched out and developed many variants on our basic model. One of the most exciting ones was our first national Deliberative Town Hall in the United States, where we had two elected officials — the Chair and Vice Chair of the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress. One Democrat, one Republican, who appeared jointly and talked about the mandate of their committee, to not just their constituents, but a whole national sample.

And something really remarkable happened. Actually, a few remarkable things happened in that session. But the one that I’ll mention right now is something that we hadn’t tested in our individual town halls, which is whether experiencing a different form of politics and hearing from elected officials who are talking civilly and substantively to each other and seeing that your fellow citizens who aren’t from the same party are not demonic mad people out to crash the Republic — whether that would have an effect on what academics call affective polarization. So we’re not talking about policy polarization; we’re talking about not liking people from the other party, not wanting your children to marry somebody from the other party, not wanting to engage with them. Because it’s okay for people to have a range of views, and if they want to be firmly conservative or firmly progressive, that’s fine. But what we can’t do is hate each other, because then we turn opponents into enemies, and that’s when democracy’s in trouble.

So the reason we never looked at that in our standard town halls is we didn’t have benchmarks for what polarization looked like in a single congressional district, but we had excellent benchmarks at the national level.

And just as a bit of background, there was a big initiative in the political science academy, and over 100 proposals got funded to try interventions to reduce affective polarization. The vast majority of them bombed out and did nothing. The most effective one got one Republican and one Democrat at a time to talk to each other over Zoom about the best thing that happened to them that week. And if they talked about politics, the reduction in affective polarization went away. And our attitude was, that’s great — sort of. But we need to be able to do this at a scale that goes beyond two people at a time, and we need to learn how to talk about politics without getting enraged with each other.

That’s why we were so excited to find from our national Deliberative Town Hall that we have what we still think is the largest-ever documented reduction in affective polarization. This wasn’t 1% of the time. It was 1,400 people. It only took an hour of two elected officials’ time to do that. And it wasn’t like we hung up the phone and surveyed them, this was two weeks later — so this is not a phantom effect. And the reductions were dramatic: it was as if we rolled back affective polarization in the United States 38 years for 1,400 people with one hour. That’s pretty extraordinary.

Anne Meeker: That’s absolutely wild. So I feel like my developing role as just a commentator and a practitioner on civic engagement and constituent engagement is I am turning into a grouch. I am tired, personally, of so many ideas that are pie in the sky or, like you said, they’re small, they’re unscalable, and they try to take the politics out of politics.

So I’m so curious. I know that we’re kind of lacking in the congressional level benchmarks on affective polarization. But I’m so curious, just your hunch from having worked in this and done these town halls for so many years — are there specific elements of that that you think are really critical? The one that stands out to me is just the fact that you were inviting people, that for many people, this is the first time they are being invited to participate. And that feels really powerful. Or is it the genuine camaraderie between Mr. Kilmer and Mr. Timmons? Can you unpack that for me? Which pieces do you think matter here?

Michael Neblo: Sure, sure. So in general, the success in terms of increased trust, political knowledge, engagement, less cynicism—all of those results that we got from Deliberative Town Halls—I think a huge part of that is exactly what you led with, that citizens feel marginalized. They feel at best like passengers on the ship of state, and some of them feel like cargo. And there’s supposedly the officer corps, right. And they become frustrated and resentful and withdrawn. But again, that is not apathy. Apathy is a lack of emotion, a lack of energy. Frustration is different. Frustration is positive energy. And that means if you can harness it, it can be redirected towards positive goods. And that’s exactly what we think is happening when they get this credible signal that this is going to be different and “I really do want to hear what you have to say.” So I think that’s number one.

Number two is just seeing two members of Congress—and, you know, Mr. Timmons was a real conservative—but hanging in there with each other and talking not just civilly, but substantively and acknowledging each other, not agreeing on everything, but disagreeing for reasons and with respect to the side that they’re disagreeing with.

When I was preparing a talk, I googled town halls on YouTube, and the first thing that came up in the autofill was “gone wrong.” Because the searches are always about spectacular meltdowns of people being horrible to each other. So partly it’s that things really have gotten worse, but it’s also partly that that’s the only thing we see. And so by giving people this vivid experience of “no, these are serious, smart people, professionals who are there to do the people’s business and are constructively discussing it,” it’s like water to a person in the desert.

Amy Lee: I would only add just one other one. I think that one of the other things that was really important to the success of that town hall was that the members were discussing, again in a bipartisan way and with really strong personal rapport, an issue of great salience to the American people, which was how to improve how Congress works.

Another result of the town hall, besides the depolarization findings, was that this actually resulted in some really pragmatically useful information for the committee and for the policies that people had supported. So there were a couple things that the Select Committee had put out to people to consider that they thought were going to totally be third rails. One was like increasing the budget for staff training, and they thought that this was going to be just like Congress voting itself a raise. This is not going to be good. Nobody wants Congress to spend any more money on itself than it already is. And that’s going to be a third rail. And the other one was, should we allow members to be able to reimburse themselves for some of their dual lodging and travel expenses and things like that? And again, people thought, this is going to get framed as a stealth raise. And they’re going to talk about how out of touch we are and this can’t be done. But the committee thought that both of these moves would be really helpful to the institution as a whole. They would keep it from being so that only wealthy people could afford to run and stay in Congress, and it would keep us from bleeding staff year after year as we lose them. If we had better—if we had more funds for retention and things like that.

So they talked about this in the Deliberative Town Hall, and they were so candid in some of the examples that they gave about how 25% of Congress is sleeping in their office. And people are like, “That cannot happen. We got to think about this immediately.” And it really did change some of the things that people thought would be third rails to where all of the proposals that they put out ended up with supermajority support, and the ones that they thought were the biggest third rails had over 90% support in all demographics across the board.

And we were able to use that information because we were able to show that the support was so broad and so deep — down to the state level, the demographic level, the urban and rural — we were able to show exactly where the strength was strongest, although it was pretty uniformly strong for all these things. And we were able to give them this information. And the Select Committee staff was able to use this to build support for some of these recommendations beyond the committee, beyond the people who participated in the Deliberative Town Hall. And several of these recommendations were implemented.

And these are small things still so far — like they are things to make Congress work better internally. But hopefully they lead to Congress working better externally and using these methods to do so.

Anne Meeker: That’s awesome. I remember seeing the press releases for those recommendations happen, so that’s awesome to hear a little bit of the backstory behind just the political work that needed to happen to make them possible.

Could we back all the way up for a second? I’m really kind of struck here: you guys talk about the history of Deliberative Town Halls, and I see a little bit of the tension here.

On the one hand, just the incredible results coming out of your work. And I got to participate in some of these town halls. I have seen them at work. They are really, truly moving — especially as a former staffer who has staffed a town hall where a fistfight almost broke out in the front row. I know how crazy [normal] town halls get. So really positive results there.

And then on the other side, Michael, hearing you talk about how the impetus for was some of those ACA town halls — it feels like in a lot of ways that we’re back here again. Politics is cyclical. We’re in this moment where disrupting town halls is the name of the game for many advocacy organizations. We have a lot of Members who are saying, hey, for genuine safety reasons, we can no longer do this. And then there’s a lot of criticism for the Members that shift to online-only town halls for some of what you’re talking about: that they’re overly controlled, the Member gets to just use it as a platform for talking points.

So I’m struck by that tension: the great potential of town halls, versus just the fact that as a whole, it seems like every ten years or so, we’re back to figuring out how can we solve this.

Michael Neblo: That’s something I’ve been thinking about quite a bit lately. And I agree that, you know, we’re back where we started in one sense. And to tell you the truth, I would say we’re worse off than where we started. And I think it’s very reasonable — and people do say this to me — it’s like, “Michael, I think your work is great. I think the institute is really important. But now is not the time to be focusing on deliberation. Now is the time to get out into the streets. Things are bad. And pretending that we can just have polite conversations about it is feeding into the dysfunction.” And I think there’s a grain of truth to that.

But there are two ways that I would respond. One draws on Martin Luther King’s letter from Birmingham Jail, which I think is the most underrated piece of political theory in American history. And that’s saying something because people read it, right? It is much more subtle and philosophically sophisticated than people often realize. I teach it all the time.

And the context is Doctor King was in jail for running boycotts and direct action, and these centrist and progressive white ministers and a few rabbis got together and published an open letter saying, you know, “We support your goals, but this disruptive politics isn’t good.” And Doctor King felt he needed to reply. And he said, you know, “Why not?” They said, “Why not negotiation?” And he said, “You are absolutely right to call for negotiation. That’s the goal of direct action.” We only go there — and I had never noticed this before, but it’s a little bit like the old just war tradition where there’s justice ad bellum before the war, where you have to exhaust every option before you go to war or it’s unjust.

Right. Well, Doctor King goes through all of these things that they tried to do with no progress. And then this is really the key one. It’s justice during war. There are limits on how you can conduct it, and it’s got to be with an eye towards restoring a just and stable peace. And so the way to do protest politics, I think, is similar. It’s not “burn it all down, win at any cost.” You can get into the streets. That’s fine. But it’s into the streets with an eye towards returning to the bargaining table, or better yet, genuine deliberation rather than just negotiation. And so even if you’re going to be focusing on disruptive or protest-based politics, I think there’s still a moment where we need to pause and consider what the deliberative activists in literature are teaching us about what we’re trying to get back to and how that can place limits on the form of protest politics that we engage in.

The second one is just tying together some threads that I mentioned before. The second reason or theme is I think we drifted in how we think about our ideal of politics, what in philosophy is called a regulative ideal. Not something we point at directly, but how we orient ourselves, what I call our North Star. And at the founding, the founders’ North Star is what I call deliberative popular sovereignty. And it sounds fancy. Popular sovereignty in this context just means that the people are in charge, that they’re ultimately the bosses. But the deliberative part means it’s not just whatever a whim of a majority thinks. It’s got to be considered. It’s got to be sustained over time. It’s got to be filtered through debate and through representative institutions. If it doesn’t do that and the people’s will is thwarted over long periods of time, that also feeds frustration, but with the pressure on representation.

After the Cold War, we kind of shifted how we thought about politics and we were really trying to contrast ourselves with Soviet and Chinese communism. And so this wasn’t the common good. It was efficiently getting people what they want. And there were trends in academia that reinforced this and said, “Common good? It’s nothing. There are individuals that want things. What government does is adjudicate between them and efficiently deliver those goods.” And that became — that replaced our North Star of deliberative popular sovereignty.

And from that perspective, the people who aren’t participating in politics, they’re voting with their feet. They don’t care. If they cared, they’d show up and compete for political goods in the market. And so I think some elected officials — not all, some of them — knew that it was frustration, not apathy. But they didn’t know how to reach everybody. And others are like, “Well, they’re voting with their feet. So I’ll concentrate on the people who are asking me for something.” But giving up on that notion of giving each other reasons and trying to point towards something like a common good — we’re never going to agree on exactly what that consists of, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have the conversation.

Deliberative Town Halls, I think, are special — to get back to your original question as to why specifically Deliberative Town Halls. I think it addresses both of those core upstream issues to the current crisis. The first one is taking some of the pressure off of the size and diversity of the electorate by bringing people together through sortition in large numbers and subsidizing them greatly and letting them work out some of their differences rather than the elected officials having to triangulate and balance and figure out.

And then the other thing it does is implicitly brings us back to our North Star of deliberation, because those discussions weren’t about how we can angle to get the most out of government. It was about what we should be doing together as a people. And so implicitly, it was taking us back to that notion of a common good. And it didn’t just snap our fingers and, “Oh, we found the common good.” But at least that was the conversation we were having. That was the standard we were holding ourselves to. And so I think that it’s really, really valuable.

That said, as I noted with Doctor King, there’s room for protest. Another thing we’re looking at is reviving this right to petition in cases when both parties or elected officials in general aren’t responsive over the long term. We’re trying to develop something like Deliberative Town Halls that are horizontal, but the work product — the end product of it — is something that’s First Amendment petition-ready, where the government is obliged to actually address it. And it’s not just a special interest group or wings of the parties presenting something, or super intense people. It’s a representative sample of a constituency or the country saying, “No, we’ve thought about this. We’ve talked about this. You guys are ignoring us. Now pay attention and here’s a proposal.” And I think there are other things we can do too. But I’ve rambled on a lot.

Anne Meeker: No, no, no. Absolutely fascinating. And I’d love to put a pin in the, in the, right to petition work and I definitely want to hear more about what’s going on there. That actually leads me to something that I really wanted to zoom in on a little bit deeper here. So we do a lot of thinking on our team about just the multiple things that any form of constituent engagement does. And you’ve touched on a bunch of them: there is gathering information, information for policymakers to support decision making. Then there’s the impact on polarization and citizens or constituents’ understandings and attitudes towards each other. And some of the symbolic work. But these are three different things from one interaction, and that’s a really complex and multilayered interaction. That’s really interesting.

But the thing I don’t know about what you’ve heard from Members of Congress, the thing that I find that I get pushback on when we’re talking about things like Deliberative Town Halls, is how to connect that information to policymaking for policymakers, bringing into the question the role of any individual Member of Congress or even pairs of Members of Congress.

The example you’ve talked about for your national Deliberative Town Hall with Mr. Kilmer and Mr. Timmons, it sounds like maybe could have been partly effective because that was a bit of a pre-political issue. We weren’t super polarized in this country necessarily on things like additional funding for staff professional development, but that’s not like abortion or immigration.

So do you have a sense for just if you’re a Member of Congress and you’re looking at the policy making cycle, where is the best place to put a Deliberative Town Hall in that policymaking cycle?

Michael Neblo: Okay. So we’ve thought a lot about this, right. If it’s to really inform policy ahead of time, I think Deliberative Town Halls can be useful at multiple stages. One is very sort of flexible ones. Where is the shoe pinching? It’s much more problem identification and agenda setting. Now obviously that’s going to work best on emerging issues or issues that are evolving pretty substantially. But that’s one place that you can do that.

Another one is issues where the party is not whipping. That’s a no-brainer. Then I think another possibility is before the parties have crystallized, basically allowing backbenchers to explore, can they be a canary in the coal mine and look for, like, the SOPA explosion? Nobody saw that coming. If they had done a Deliberative Town Hall, everybody would have seen that coming. It would have been a neon flashing sign in a Deliberative Town Hall. And the flip side, the positive flip side of that is opportunities for low-hanging credit claiming and pleasing constituents that you didn’t realize was important to them. So I think there are lots of those, right.

Another big one is — once, let’s say we went pretty deep and ultimately couldn’t do it, but we were working with a committee, a substantive committee. And the committee had been working for years and basically worked up three viable, over-the-bar responses to a particular policy problem. I won’t tell you what it is so I don’t identify the committee. But the chair was more or less like, of course he had his personal views on which one would be best, but it was much more important to him that one of those three passed the floor. And what Deliberative Town Halls can do in that context — let’s say a national one — is give a lot of good information about what the considered views of the public are going to be among them. That can then be conveyed credibly to their colleagues to facilitate choosing the one and getting it over the bar on the floor. So I think there’s value there. And that’s deeply connected to policy. And then the last one that I’ll mention for now, is even after a vote, once things are crystallized, there’s value in an elected official explaining why they’re doing what they’re doing or why they did what they did, rather than waiting for the next election and bundling the 10,000 things they did over the last two years together into one summary judgment.

But explaining to people, “I voted this way because...” Right. And what’s the value of that? First of all, I think that’s just how representative democracy is supposed to work. But beyond that, we find that people are much more willing to give their elected official a certain amount of slack, even if they disagreed with the vote, if they can see that it wasn’t just craven caving. This is a sensible rationale. I weigh things differently. But I don’t think it’s just the corrupt elite blocking us out here or catering to the other side and their crazy ideas. It’s like, “No, we disagree. I lost this time. Let’s come back and next time I’ll hang in there and hopefully I’ll win.” Right? So even if it’s not going to change policy, if it’s after the fact, I still think there’s enormous value in shoring up representative democracy.

Amy Lee: And I was just going to say that, yes, it’s not even only that the Member—that people trust the individual members more, or are more likely to agree with it so they don’t have their trust in government kind of slowly worn away by the dominant story, which is just that elites are selling you out and they’re all the same, really, and all those things. This gives an opportunity to kind of really understand what the real reasoning is.

I’ll just second, very briefly, what Michael said about we really think that committees are the most important place for this to really inform policymaking, just because of so much congressional procedure and process. So yes, there is a limit to what any one individual member can do. But if we can work with both halves of a committee to just get them nonpartisan, non-biased information from the full breadth of their constituency… we now have the statistical methods — Michael can explain them. I cannot. But we now have methods to where we can actually explain for all 435 districts of Congress what constituent opinion is on a particular issue, just from doing one national sample with 2,000 or so people. This is so different from any other issue where it’s almost impossible to do national polling on any but the most kind of top-level issues. It’s usually done a lot of times in partisan ways that aren’t necessarily 100% scientifically credible. And when it comes to knowing what people in your district think, polling at that level is almost unheard of. So the idea that we can produce that information for all 435 members of Congress is, I think, really exciting. And that’s how I think we have impact on policy.

Anne Meeker: That is absolutely fascinating. We’re running short on time, so two things I really want to make sure we talk about. Neither are completely fair to ask you both, but I’m going to do it anyway. So the first is capacity. So I know the other big push back when I am talking to members of Congress, I’m talking to congressional staff, you know, and talking about super cool stuff in the world of deliberative democracy and constituent engagement. The answer is always, that’s fabulous. But as you said up top, Michael, we have 17.5 staff to handle a district for 780,000 people, my phone is ringing off the hook, I have a thousand cases open, the floor schedule is crazy… Like I just can’t try something new. So because you two have been really involved in the “Fix Congress” world, in the modernization world, I would love any thoughts you have on the role of congressional capacity in this kind of experimental work. And then where do you think it would be most helpful for Congress to invest in its own capacity?

Michael Neblo: That’s a great question. And it is way bigger than Deliberative Town Halls, right? It’s mind boggling to me that the legislature of the wealthiest, most powerful country with an unbelievably staggering range of complex policy issues to deal with has hobbled itself so badly and is relying on brilliant, committed, but wildly overworked people who who don’t make enough money to raise a family in Washington, DC.

And there’s just massive drop off in institutional memory. That was one of the really exciting things about the Select Committee Deliberative Town Hall, because the, the, the biggest move, it was like a 42 point move in supporting, basically allowing Congress to properly fund itself and to pay their brilliant, hardworking staff a living wage for Washington DC.

It was a sea change. It went from massive supermajority against to very solid supermajority for in every single congressional district.

Amy Lee: It was almost 90%.

Michael Neblo: Yeah. Every single congressional district moved into the majority position. That’s stunning. Right. And it means that the citizenry aren’t fools, right? The businessmen and women were speaking up saying really, that’s how you manage your human resources? You know, that’s insane, right?

Okay. So one thing is just to say we absolutely get that. And it’s true. It’s just true. The staff are wildly overworked. The Members are overprogrammed. Now, what we can do for now ourselves is we try to make it very, very turnkey for the Member. It’s like an hour and a half — the hour in there, and maybe a half an hour in prep. That’s about it. And for the staff, it’s going to be a little bit more than that, but not a ton, is what we shoot for. Even then, though, it’s something new. And there’s uncertainty and people are overworked.

But you may remember, briefly, the House Admin made an internal allocation. There was a common pool resource for lots of things — hiring underrepresented categories of interns for paid internships and lots of things. And one of them was Deliberative Town Halls. So as part of this APSA [American Political Science Association] task force that I’m a part of, one of the recommendations we’re making is that Congress properly fund itself in general, but in particular, around increasing its capacity to do effective and broad citizen outreach. And that could hopefully include Deliberative Town Halls as one component.

To the extent that that’s not forthcoming, we’re hoping to get civil society to pitch in. And one proposal we have out there in the short term is simply to just get a college graduate, a recent college graduate on the ground in DC who could go into an office in person and further subsidize and lower the costs and lower the risk. Like you’ve got somebody on the ground right there who can troubleshoot for you, can walk you through it, who can bring equipment, who can do all kinds of things to make it turnkey. And then the goal would be eventually to ramp that up and make this a routine part of consultation and citizen engagement.

So, but it just is a problem, you know. But it’s part of—to my mind, especially after the Supreme Court decision basically heavily reining in the administrative state, it’s all back on Congress now. Congress simply cannot do this. It’s absolutely impossible under current funding, internal funding. I mean, we’re talking about doubling or tripling if we really want to bring if we really, really want to respect that Supreme Court decision, it’s not even a small increase.

Anne Meeker: I’m so glad you drew the connection between Loper Bright and deliberation, and constituent input. I also want to ask about political science. We’ve talked a little bit about previous approaches in political science, and the more “realist” approach after the Cold War that really took a very negative view of the ability of individual constituents to participate in their own democracy, constituents’ ability to remain informed, contribute informed opinions to policy discussions. One thing I have always loved about your work, why it was so much fun working with you guys, is that faith that you guys maintain in constituents. This is a really positive take on what constituents are able to do and on the value of what constituents can contribute.

Again, I keep coming back to tension. There’s always a little bit of tension, I think, between some of the political science-y, theoretical understandings of Congress, and then understandings of Congress that are really informed by that practitioner view. And I think you guys do such a beautiful job of melding the two, so I’m curious: where do you see political science going as it relates to Congress, as it relates to Congress’s maintenance role in strengthening American democracy? Are there things you’re excited to see the academy do? Are there new approaches you’re excited to see the academy take? I’d love to just have you forecast what happens next.

Michael Neblo: Yeah, yeah. So that’s a great question. I alluded to this before, but the previous president of the American Political Science Association, a fellow named Mark Warren, convened a task force on democratic backsliding and innovations to address democratic backsliding, primarily in the United States, but the global phenomenon as well. I think there are 12 of us on the task force, but I was asked to participate, and everyone was given a sort of portfolio of things. Mine was strengthening the representative relationship.

And as far as how political science thinks about the citizenry, I guess I would say it’s not gotten that much better across the board, I think. And that’s because the basic facts are true, that when it comes to factual knowledge and ongoing engagement with politics and policy, the vast majority of citizens are low to zero. But we posed a different question. That’s as things stand right now. The question is, given the means to actually contribute in subsidized mode of thinking, where there’s actually a reason to invest some time and energy in this, and an opportunity, a specific targeted way, that they can contribute to democratic governance —

You referred to it as faith, and it is kind of faith. But faith in a particular way, I think: of faith, for what it’s worth, in both religious and political terms — not so much as a factual belief, but a willingness to act on the presumption that the thing that you have faith in is operative. Maybe on a deep level, it’s true or not true, but I’m going to act in a way that flows out of that faith. And then you see how life goes, or you see how politics goes. And if it goes a little bit better, then your faith was rewarded in a certain sense. And again, trying to get what’s really true all the way down there. It’s like, is this working? It’s very practical. It’s surprisingly practical for an academic, right?

And so in that sense, I think you’re right. We do have faith in the average citizen, but I don’t think it’s a blind faith or willful, pollyannaish optimism that doesn’t look squarely at the facts on the ground which, as I noted, most people, most of the time on the vast majority of things, know very little to nothing about politics and don’t of their own accord engage. It’s just that we think that’s the wrong question. The question is, can they step up to the plate when they’re called upon and given the right opportunities? And that was the faith that we were willing to act on.

And, man, has that been rewarded and validated, because the answer is an emphatic yes.

And even the people who started out with the least political knowledge, the least political resources, what looked like the least motivation and interest — they were the ones that gained the most. And it just keeps happening. They want to be part of the democratic community. They want to be good citizens. And when you show them what that could look like for them and subsidize it and give them opportunities, they line up and they train up and they stand and deliver.