Parliaments as Living Information Systems

Understanding legislatures as evolving institutions shows why digital transformation requires coordinated global action

BY BEATRIZ REY

Legislatures are information-processing organizations. I first learned to see them this way while studying Keith Krehbiel’s work for my PhD comprehensive exams in the mid-2010s. For Krehbiel, the need to acquire and manage policy expertise underpins legislative development. Legislators create institutions, such as committees, party caucuses, and even plenaries, not simply as arenas of debate, but as mechanisms that generate, filter, and distribute information. In that framework, information was scarce. Or so we thought.

Krehbiel’s perspective has stayed with me since I completed my degree, but my understanding of legislatures through it has changed. Legislatures are not merely information-processing organizations — they are living information-processing organizations. The word living matters because it makes visible an essential fact: legislatures evolve alongside their political, technological, and social environments.

I believe we are living through the third great turning point in this technological evolution. The first came with the advent of personal computers. The second arrived with the rise of the Internet. The third is unfolding as I write: artificial intelligence has changed and will continue to change everything.

In early December, at the conference organized by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), the Westminster Parliamentary Association, and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, this reality became increasingly difficult to ignore. At times, even uncomfortable. Uncomfortable because it forced parliamentarians, their staff, and those of us who work with and/or study legislatures to confront a twofold truth.

First, legislative processes are not operating close to optimal capacity from the perspective of Members or citizens. As one Member remarked in the final plenary session, legislative politics is often intensely bureaucratic. Bills move slowly, rarely reach approval, and are frequently reintroduced when new sessions begin. Time for substantive policy debate is limited. Constituent engagement is slow or inconsistent, with emails disappearing into overloaded inboxes, and legislators struggling to balance committee work, plenary duties, and time in their districts.

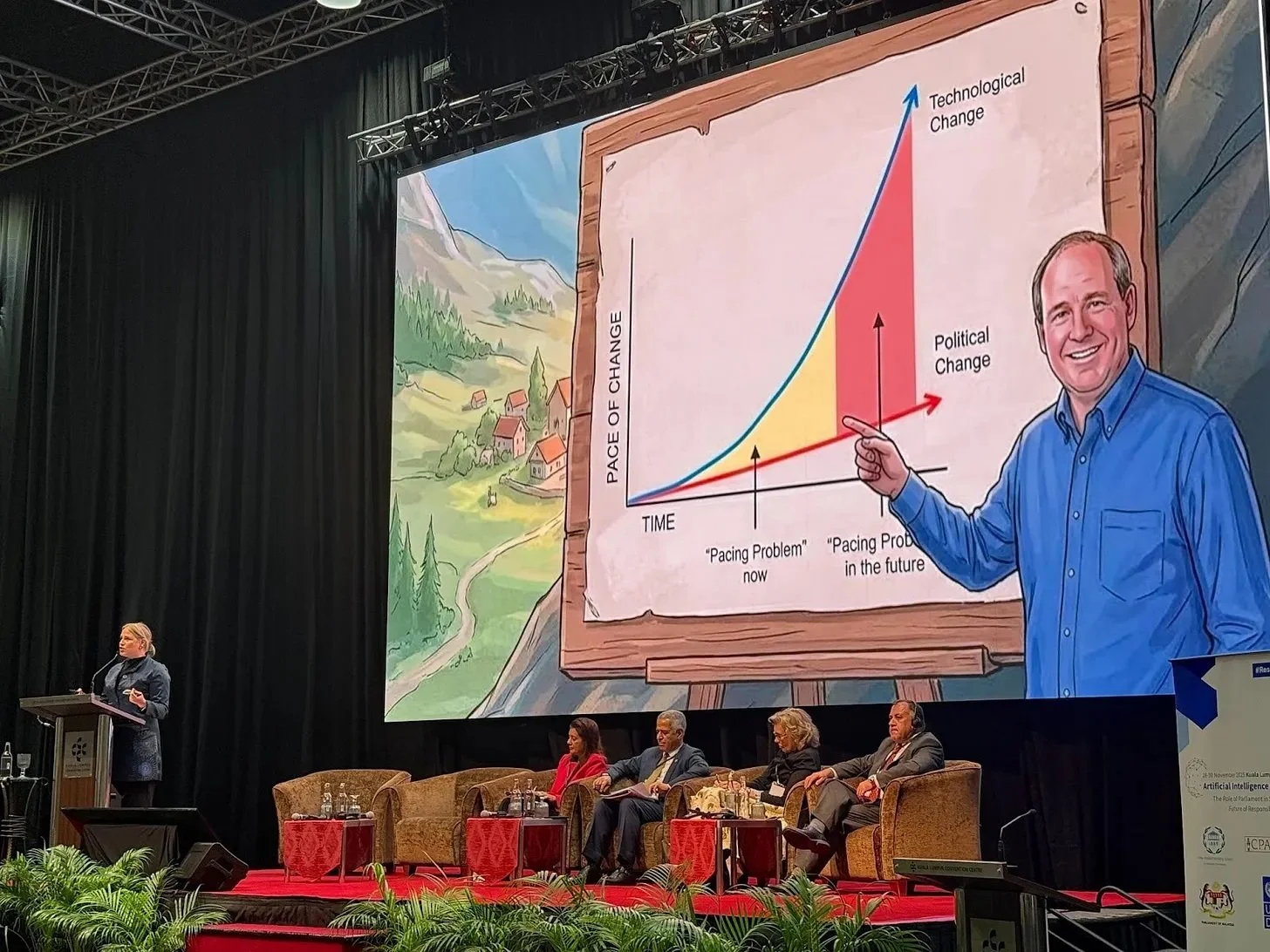

Second, artificial intelligence is rapidly developing, creating what Arizona State University Professor Gary Marchant termed the “pacing problem”, referring to the increasing gap between technological and political change. Over time, the area in the graph pictured below will continue to increase because of AI unless we collectively take action. In Kuala Lumpur, the meaning of taking action took several forms, but I want to focus on a specific point: how parliaments can draw on coordinated support from international institutions as they move from digitization to digitalization, and ultimately to digital transformation.

Marci Harris, POPVOX Foundation’s cofounder and executive director, presenting the idea of the “pacing problem” in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Digitization

The advent of personal computers began in the 1970s, culminating with the launch of machines like the IBM PC (1982), the Apple Lisa (1983), and the Macintosh (1984). For information-based institutions like parliaments, this moment could have marked the beginning of a systematic digitization of their core processes: the conversion of analog records, workflows, and legislative data into machine-readable formats. Instead, most legislatures treated computers as administrative tools rather than as an opportunity to redesign how information circulates inside the institution. The result was a missed opportunity. In other words, parliaments never digitized their knowledge base. Many have yet to fully convert from paper systems. This foundational gap continues to shape the limitations of legislative technology today.

Digitalization

In 1991, Tim Berners-Lee released the World Wide Web, including the first browser and web server, creating a linked system for sharing information and marking the second major technological evolution. The Web did more than place information online; it made digitalization possible by enabling activities to be rebuilt around interoperable data. Yet, once again, parliaments largely treated the Web as a new channel for documents rather than an opportunity to redesign how information flows through the institution. The second major technological milestone arrived without a corresponding institutional transformation.

A similar opportunity emerged with social media platforms in the 2000s. For the first time, citizens could collectively voice preferences, debate policy, and organize at scale in digital environments. This transformation could have spurred parliaments to redesign how they capture, process, and act upon public input. Instead, most legislatures treated social media as a communication channel for individual politicians rather than as an institutional tool for representation. The participatory revolution happened outside of parliaments, not within them.

Digital Transformation

Finally, although artificial intelligence has existed since the 1950s, the combination of big data and machine learning in the 2000s and, more recently, the emergence of large language models in the 2020s marks a third technological era. This new moment represents the threshold between digitalization and digital transformation. While digitization converted analog records into digital formats and digitalization used interconnected data to reshape activities, digital transformation refers to the broader institutional, economic, and societal impacts that emerge when technology reconfigures core functions.

For parliaments, AI is therefore not simply another tool, but an opportunity to complete a transformation that previous technological waves made possible yet never fully realized. If adopted strategically, AI begins to function as a parliamentary tool: it organizes information flows, structures legislative work, and mediates the relationship between representatives and constituents.

However, the reality we encountered in Kuala Lumpur is reflected in the numbers themselves. Forty-one percent of parliaments are still in the early exploratory stages (testing pilots, building basic capacity, and drafting initial governance). A further thirty-five percent report only informal use by individual Members, without institutional guidance or standards. Combined, these figures show that none of the surveyed parliaments are in a mature phase of digital transformation — suggesting that AI remains a tool in practice, not yet an institutional layer.

This is a moment in which parliaments themselves must take the lead in coordinating their digital trajectory, drawing on support from organizations such as the IPU, CPA, UNDP, and POPVOX Foundation where useful. The task ahead is threefold. First, parliaments need to complete the digitization stage, ensuring that records and core processes exist in digital form. Second, they must help those that have digitized progress into digitalization, where data becomes interoperable and parliamentary activities are redesigned around it. Third, parliaments should define an institutional framework for the use of AI, enabling digital transformation on their own terms, regardless of their starting point. In other words, digitization should be undertaken with digital transformation as the end goal, and digitalization should be steered toward that same institutional outcome.

The work ahead is significant: without sustained collective action, the third technological evolution may unfold without producing the institutional transformation that parliaments need.

Modern Parliament (“ModParl”) is a newsletter from POPVOX Foundation that provides insights into the evolution of legislative institutions worldwide. Learn more and subscribe at modparl.substack.com.